Critiquing Surveillance in San Diego with a Flying Photo Lab

08 Nov 2022

Welcome back to our regular newsletter. Today we hear from working artists beck and Katie, who are launching Floating Photo Studios over San Diego’s Hilltop Community Park over the course of four weekends. This project creates an environment for talking through and learning about the interrelated issues of surveillance, photography, power, and place. Park goers are invited to fly a kite with a camera, take pictures from the sky, and print them as postcards. On the last day of the project, the postcards are dispersed to everyone who has opted in to participate.

Artists Katie and beck during a test flight at Hilltop Community Park, San Diego

The Working Artist’s Perspective

By Katie and beck AKA @floating_photo_studios

“Have any of you been to the Horizon before?”

For the past six years, we have been collaborating on art projects interrogating issues of photography, power, and place. We performed as a tour guide company, Horizon Tours, made drawings on road trips, and measured the horizon with string.

Katie performs as one half of Horizon Tours in Amagansett, New York in 2018.

So of course when I (beck), noticed a camera installed in a streetlight above my head as I waited for the bus near University of California, San Diego, I immediately texted Katie. We both thought it was weird and way creepy. We mused about performing for these cameras and discovered the Surveillance Camera Players, a group who performed plays such as Waiting for Godot for New York City’s surveillance cameras. While researching the issue in San Diego, I came across a map in the San Diego Union-Tribune of all of the active cameras in the city, confirming that I was indeed regularly commuting under the gaze of several different ones. I found a town hall event sponsored by the TRUST Coalition. I started following the issue and joined wherever I could.

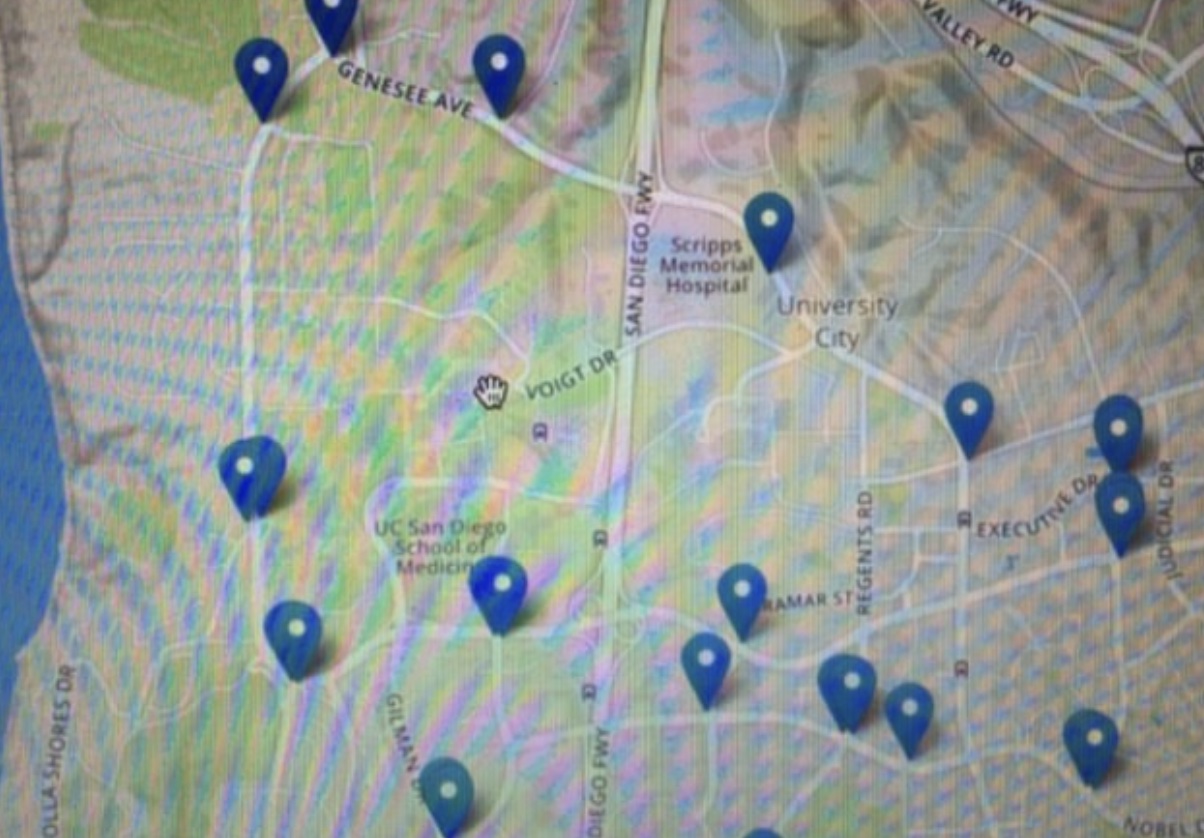

A map of new smart streetlights that can record audio and video 24/7 near beck’s graduate school campus, according to a map published in the San Diego Union-Tribune.

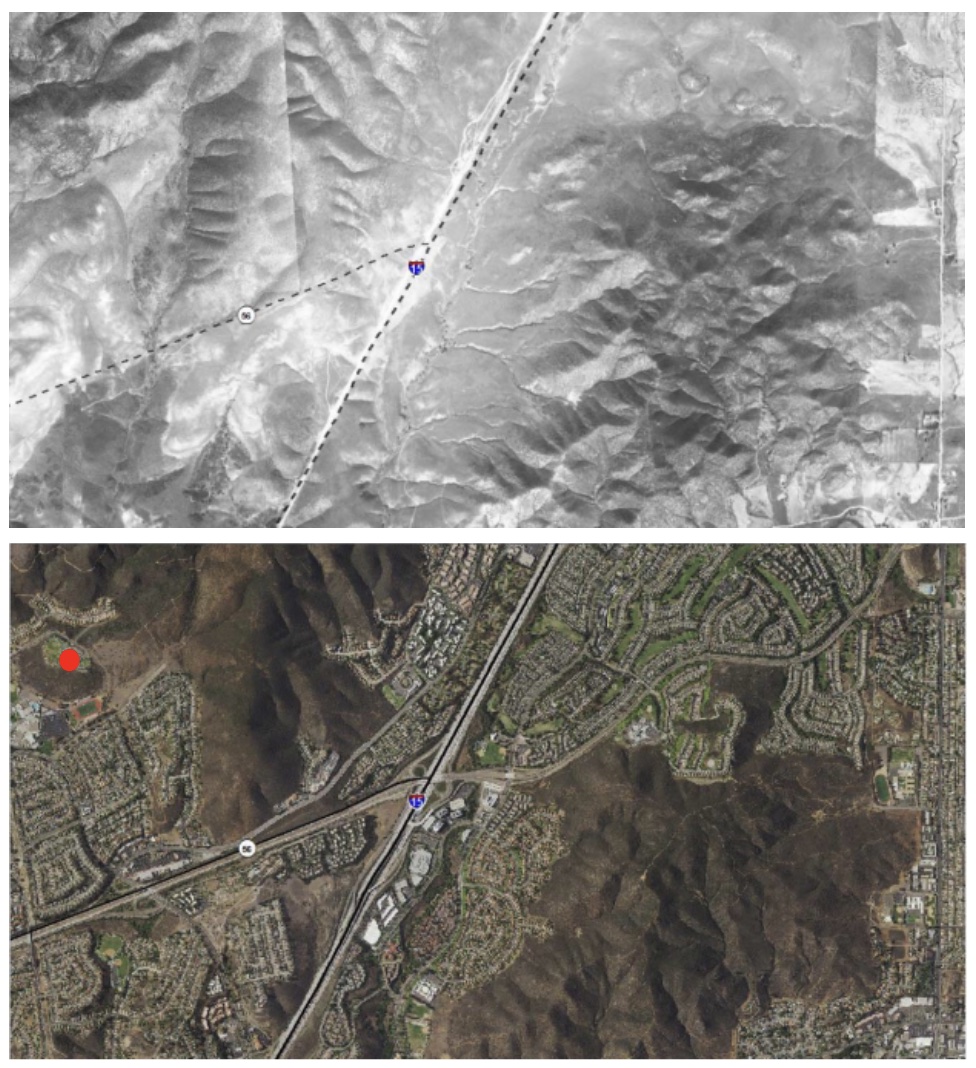

Later that year, we were commissioned by the San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture’s Park Social initiative to design a temporary, site-specific public art work in a park within council district 5, which includes northeast San Diego and the communities of Rancho Peñasquitos, Scripps Miramar Ranch, Rancho Bernardo, San Pascual, and others. While researching the district, we came across a number of aerial surveys of the area that had been used as a part of real estate development and planning. This top-down view reminded us of one of our favorite essays, Free Fall: Notes on Verticality, by Hito Steyerl. In the essay, she describes how the shift to satellite imaging has erased the horizon as the organizing principle of looking at land: “One of the symptoms of this transformation is the growing importance of aerial views: overviews, Google Map views, satellite views. We are growing increasingly accustomed to what used to be called a God’s-eye view.” Steyerl goes on to discuss how the aerial perspective risks exacerbating militant uses of imaging and visual languages of domination. However, she suggests, there may be something special to this visual paradigm if we can attune to the complexity and distortion it affords—an instability that “promises no community, but a shifting formation.”

The area surrounding Hilltop Community Park in the 1940s, and 2014, approximate site of park marked with red dot.

When we visited Hilltop Community Park in Rancho Peñasquitos, it was love at first sight. Located adjacent to Black Mountain Open Space Park, Hilltop had stunning 360 views of the surrounding community and a vast, flat, treeless circular field. This makes the park a favorite for flying kites. This got us thinking: what if we could fly cameras on the kites as an entrypoint to thinking through these interrelated issues of power and photography?

An image made by a participant’s kite on October 30, 2022 showing the hilltop, an orange wind piece made by Austin Wade Smith, and park goers and kite flyers scattered around the field. Along the horizon, a blue kite flies with the Floating Photo Studios logo, made by San Diego Kite Club member Rick Sturgeon.

Floating Photo Studios (FPS) is a community photo lab popping up over the course of four weekends at Hilltop Community Park. Park goers are invited to fly a kite with a camera, take pictures from the sky, and print them as postcards. They can keep a postcard for themselves, and also offer one to a growing community aerial archive. On the last day of the project, the postcards are dispersed to everyone who has opted in to participate.

Jihan, a member of Tech Workers Coalition San Diego, and beck get ready to attach a camera to the string of a kite.

Flying a kite is a physical activity that requires constant collaboration with the pull and push of the wind, maintaining gentle tension on the string to keep the kite afloat. It can be awkward, silly, and difficult. Language of group play and coordination spreads between us: “Alright, who wants to launch? And who can steer the kite line? Who wants to hold the camera? And for whom is this image we’re making?” Care and attention is required to fly kites at Hilltop, and we think about what it would be like if our imaging technologies required the same kind of public engagement to operate.

Katie Giritlian, Maria Antonia Eguiarte and Arlene Mejorado take a group photo, smiling up at the kite camera.

One person holds the string of the kite, while another holds an orange filter over their face, and a third takes the photograph using a phone app connected to the kite camera. We brought props for park goers to play with in their photographs: orange filters, shiny mylar, and curtains became tools for obscuring and revealing.

A group becomes invisible to the camera by huddling under a colored parachute.

FPS aims to model an alternative that is joyful, expressive, collaborative, and fun, while asking what kind of world is necessary to practice these loving modes of observation?

We are delighted by the imperfections of the images produced by our kite-cameras. As they are used, they fly high in the sky and tumble low to the field, dragged along the surface collecting grass and dirt. The lens carries the traces of these encounters, and occasionally bits of the earth block the visibility of the land below. The scale of a piece of grass becomes equal to a human standing nearby.

We pick the camera back up and anchor it to another kite. As we slow down the assumed automation of photography, we look around the park and see the group that made this joy possible. We see members of the San Diego Kite Club pointing and looking at the sky. We see members of the Tech Workers Coalition sitting on the grass and dispersing zines for organizing against surveillance in San Diego. We see our loved ones writing messages on a scroll of blue paper to be seen from the clouds.

In this image, Kirstyn Hom, a local artist, holds up a piece of mylar to the camera. The camera is unable to capture Kirstyn’s image and instead sees its own reflection.

There were more images made that will never be shared here, or anywhere. A family photograph. A very cute dog close-up. The authors of these images did not want them to be shared. As artists, we felt a small internal pang—such a beautiful photo! But the beauty of it does not necessitate its sharing, and the fact of its existence doesn’t mean it should be automatically made available to all. These types of agreements are central to the project and the way we navigate consent and sharing.

We hope to use this project to engage the PQ community in reflection about how images of themselves and their community are related to systems of power in our city. On the back of the postcards are reflective questions for participants who want to go a little deeper. One asks: “What does ‘loving observation’ look like for you?”. The response: “Nothing about us without us.”

Our Floating Photo Studios will fly for its final weekend at Hilltop Community Park on 11am to 2pm on Sunday, November 13, 2022. You can follow our archive on Instagram at @floating_photo_studios. Thank you to Tamara, Erik, and Danny for the conversation that led to this narrative.