This new pandemic phase: back to the office with disparate solidarity

11 Jun 2021

As the pandemic enters a new phase, some offices are beginning to open up again and employers are pushing for things to return to normal. Tamara Kneese reflects on recent developments in tech worker organizing, and considers how new forms of solidarity forged remotely through digital channels could evolve as “we” “return” to “the” “office” and continue organizing.

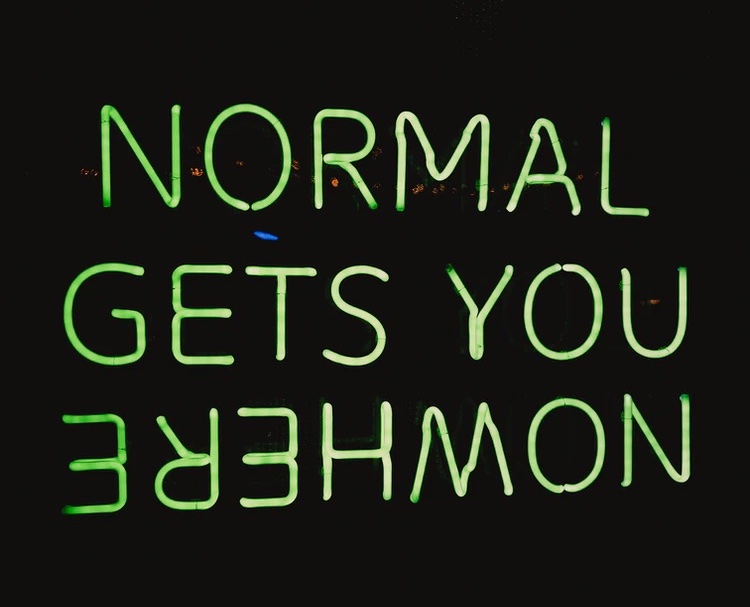

Why go back to normal? / Source

The Worker’s Perspective

This next phase of the pandemic requires a new orientation to organizing. What does a “return to the work” really mean? Under lockdown, workdays extended into evenings and weekends. Kitchen tables and beds became workspaces as many of us balanced caregiving, homeschooling, and domestic duties in between meetings. As lockdown ends in some places and many offices “open up” again, what happens next for building cross-collar solidarity and worker power in different “workplaces”? What helps, what hurts?

In our “Tech Under a Pandemic” series, four workers were organizing in wildly different workplaces. Management used the crisis to demand more output and make cuts, while workers pushed back on unreasonable expectations. At the start of the pandemic, many physical workplaces shut down save for a skeleton crew, further dividing an already stratified workforce. Janitors, catering staff, and other service workers were the first to be furloughed or laid off. Contract materials engineers did not get clear rules for working from home with employer-owned lab equipment, and often could not access files because of security protocols. Meanwhile, many white-collar managers were told they could continue to “WFH” indefinitely, making the future for campus contractors less certain, especially as large companies like Yelp!, Pinterest, Salesforce, and many more announced office closures and downsizing.

Despite these new or exacerbated structural problems, the Zoom-centric environment for remote work – and more importantly, for remote organizing – provides some relief for workers who are also caregivers. It’s labor in itself to attend physical meetings when you have to pick up your kids from school, work several jobs, or care for elderly parents; the most visible organizers in a physical environment are often those who have the luxury of time to dedicate to the cause. Artist and activist johanna hedva describes how disability, illness, and caregiving duties make it difficult for everyone to engage in the most visible forms of protest, like marches or actions. Some academics have argued that virtual conferences and classes, if done right, could become more accessible, and similarly, remote organizing may also mean that more people are able to participate. Along with crowdfunding campaigns for gig workers who were injured or killed on the job and Tech Worker 4 Tech Worker mutual aid, workers in the “gig” economy mobilized against Prop 22, with Rideshare Drivers United drivers and supporters using text banking apps and social media campaigns to reach voters. Volunteers and drivers met one another over Zoom trainings, just as remote union and coalition-based solidarity meetings at my own university workplace helped me connect with full-time and part-time teaching colleagues I had never met IRL along with librarians, program assistants, service staff, and clerical workers from across the university. Sure, Zoom fatigue is real, and many of us are tired of teaching and giving talks into the void, but even though in-person meetings and events are becoming feasible again, we shouldn’t forget the organizing potential of connecting through digital means.

After all, organizing is about building personal relationships over time. It’s more than just public events and viral petitions; the unglamorous labor of phone banking, committee work, and filling out spreadsheets is just as crucial to collective action as the work that gets the spotlight. Like most workplaces, tech workplaces allow certain workers to hold informal, in-person meetings. These spaces are also intimately connected to employee surveillance and strict hierarchies, where workers are segregated by employee status, even when they work side-by-side on the same team. TVCs (Temps, Vendors, and Contractors), from contract coders to custodians to bus drivers, receive different treatment than their full-time colleagues. Contractors also face job insecurity, a problem exacerbated for workers on employer-sponsored visas, which can make organizing all the more dangerous. Workers are deliberately kept on short-term contracts so the company can maintain a high turnover rate, discouraging people from forming strong bonds and collectively organizing. Microsoft used this tactic back in the 1990s, which the WashTech union sought to push back against by uniting temps from a variety of sectors. But campus work environments also provided opportunities for shows of solidarity. There have been several cases of FTEs supporting the organizing efforts of their TVC colleagues: giving them access to buildings, or posting messages of support after retaliation from management, such as in the case of Facebook’s Filter Digital contractors forced to choose lower wages or lose their jobs.

For decades, not just before the pandemic, white-collar workers in corporate offices have had opportunities to learn from workers organizing in decentralized conditions. Domestic workers, home-based pieceworkers, gig workers: such workers have long recognized that looking out for each other is the only way forward. Consider self-organizing in local mutual aid networks in Indonesia; holding micro bosses accountable with Turkopticon; or realizing worker power with a co-owned cleaning app. A vibrant tradition of collective resistance and action exists in the less glamorized parts of the tech industry, including the Latinx and Asian-American electronic manufacturing workers in Silicon Valley in the 1980s and 1990s, as documented by ethnographer Karen Hossfeld; janitors who collectively organized at HP; and the temporary office workers featured in Processed World. Today, digital communication channels like Facebook groups, Google docs, Slack channels, and WhatsApp groups facilitate organizing and social bonds — even though those same tools are often used to surveil workers. Disparate solidarities are just as real.

Likewise, tech labor organizing could follow the lead of immigrant women garment workers who fought for bargaining rights in the early 20th century. There are eerie parallels between garment piecework and modern-day gig work — as Veena Dubal explains, both use “a deceptive cultural narrative that makes it appear possible to earn while simultaneously attending to unpaid domestic work.” Winifred Poster details the ways remote receptionists and virtual assistants in India tend to their children and other domestic duties while they perform their work. The refusal of work can be a key feminist tactic, as articulated by the international Wages for Housework movement in the 1970s. Home-based workers who provide the essential behind-the-scenes labor that make production possible, can make themselves more visible by collectively disrupting or halting workflows. DoorDash drivers’ #DeclineNow strategy, whereby they refuse to take on cheap orders, is in this vein. Theirs is a kind of refusal that should be recognized as much, if not more so, than the #TechWontBuildIt refusal of white-collar FTEs.

In the past, TWC’s Learning Clubs offered a space for people to meet workers from different kinds of workplaces and share their stories in an informal environment. What does the digital version of that, or as Melissa Gregg calls it, “the great water cooler in the cloud,” look like in practice? One strategy, aside from virtual meetings or asynchronous chats, is to engage in one-on-ones that are more focused on understanding a person’s perspective, rather than assessing their usefulness to a formal organizing plan. In other words, one-on-ones within union organizing are often a kind of pseudo-scientific sussing out in order to identify who could be useful as an organizer, who is an ally, and who is on the fence (or potentially a mole for management). For researchers, these interviews might be done for the purpose of publishing a paper. But if workers from different positions and sectors within tech were to interview each other and engage in meaningful conversation, that could be a step toward building solidarity.

As the pandemic has made clear, people doing tech work everywhere from hospital back rooms to CEO offices, are now platform workers, to varying degrees. Either we build it for work or we use it for work. Teachers and students have grown accustomed to using Zoom, Blackboard, Canvas, and, unfortunately, surveillance tools like Proctorio. Retail workers are increasingly pivoting from brick-and-mortar stores to e-commerce. Food service staff are negotiating with iPad apps and QR code menus in an attempt to uphold COVID safety protocols, while also negotiating with delivery platforms like DoorDash and UberEats. Delivery workers and restaurant workers may find they have more in common than they realize: if almost all work is now attached to platforms, what are the limits of the categories of “tech worker” or “platform work”, and how can we begin to map out the contours of different types of work?

One consequence of the pandemic may be that even workers who see their positions as safe will find they have more in common with their precarious colleagues than they know. As Fred Moten once put it, as only he can, ”The coalition emerges out of your recognition that it’s fucked up for you, in the same way that we’ve already recognized that it’s fucked up for us.” There have been numerous stories of layoffs of white-collar employees at well-known tech companies, sometimes even despite record profits under the pandemic. While often presented as an innocuous act of corporate restructuring, layoffs are also a well-established tactic when workers start to form unions or otherwise self-organize, as happened with data scientists fired while organizing at Civis. Through ongoing conversations about working conditions and shared interests, FTEs and white collar TVCs may find they share many concerns with gig workers and other campus contractors. One lesson from the pandemic is that no matter how much employers want to return to “normal,” “normal” may not be what is best for workers. There’s no turning back now.

This essay was edited by Wendy Liu, Jesse Squires, and Danny Spitzberg.

Like what you’re reading? Got feedback or ideas? Email twcnewsletter@protonmail.com with the subject line “Feedback.”