The System is Rigged

28 Jun 2021

Today we share excerpts from an oral history with Dr. Richard Hudson of the IBM Black Workers Alliance. The interview explores how exposing a rigged system creates space for solidarity; how workers used the IBM BWA-NY Newsletter as an organizing tool; and how an unsuccessful NLRB case nevertheless proved useful for future generations.

'Weaving'. Photo from an IBM factory in Poughkeepsie, New York, by Ansel Adams, 1952. / Source

The Worker’s Perspective

by ann haeyoung

Dr. Richard Hudson was an employee at IBM from 1963–1980. Between 1978 and 1980, he was President of the New York chapter of the IBM Black Workers Alliance (BWA), during which time he wrote and edited the IBM BWA-NY newsletter. While at IBM, Dr. Hudson also received his PhD in Sociology. After leaving IBM, he taught Sociology at Mercy College.

In 1961, President Kennedy put forth Plans for Progress, an initiative for major corporations to voluntarily integrate their workforce. IBM was one of the first companies to join the program, and Dr. Hudson cites it as a possible factor in his hiring. However, much like in today’s workplaces, bringing Black employees in the door did not mean equal treatment once they were there.

To improve working conditions for himself and his fellow workers, Dr. Hudson filed dozens of discrimination complaints using IBM’s “Open Door” letter policy, which allowed employees to write letters directly to senior executives, including IBM Chairman Frank Cary. Dr. Hudson also filed complaints with the EEOC and the NLRB. Over the years, he helped workers win back pay, reverse termination decisions, and receive promotions that they had previously been denied.

In 1979, an anonymous fellow worker sent Dr. Hudson a salary distribution chart which showed how much less Black workers were being paid. Dr. Hudson shared this information with other workers at a BWA meeting. When IBM fired him, on the grounds that he had shared confidential material, he filed a suit for wrongful termination with the NLRB. His case had legal merit: sharing salary information amongst workers is protected by law, and Dr. Hudson had obtained the information legally. Still, the judges sided with IBM 2-1. Reading the decision today, it’s hard not to escape the feeling that the courts were simply stacked against him.

Dr. Hudson brought people together, informing them of their rights and giving them the confidence to fight back against IBM. Even after leaving IBM, he continued advocating for others as an educator and community member. His work has a lasting impact we can feel today.

Dr. Hudson shares his first impressions of IBM.

IBM hired me in 1963. I was very happy because I was going from a system [at the U.S. Post Office] based on seniority and IBM said, “We have a merit system. If you work hard and if you’re a good worker, you’ll get paid accordingly and we’ll promote you accordingly.” At the age of 23 you want to believe in this stuff. I really did to some extent. It took me about eight months before I figured out something was very wrong.

Dr. Hudson recounts an early experience of discrimination.

I was in an area working with about another 15-20 other workers. I was the only Black IBMer of the group. And I was very upset because no one would help me as I was learning the job. But I thought that was okay, I’ll do it on my own.

I was in an area that was responsible for building test equipment. And they had three guys working on this special project within the group. And the lead technician came to me one day and said to me that they had fallen behind on the project and needed someone else to help them. He asked whether or not I’d be willing to work with them. And I said, “Yes!” He said to me, “They don’t want to work with you.” I said, “That’s not my problem.”

So I was assigned to work with these three guys. Every morning I had to meet with one guy who had the updated specs to make sure that my schematic agreed with any changes. The problem was that when I walked over there on the third morning, the guy just blasted on me. He just went off on me. And everyone heard him. And part of the response was that I shouldn’t be there anyway.

But after he spoke out loud to me in that manner I just said, “Okay.” I just walked away from him. I went to the manager and said, “You heard what happened outside.” He acted as if he did not hear it. I said, “You heard him. Everybody else heard him. You heard him too.” I said, “Now, you have a problem. I don’t.” Because I was told there was a problem with them. I’m doing what I’m supposed to do.

After each instance of racial discrimination from his co-workers, IBM would transfer Dr. Hudson to a different department. Rather than resolve the problems he raised, management made it clear that they thought he was the problem.

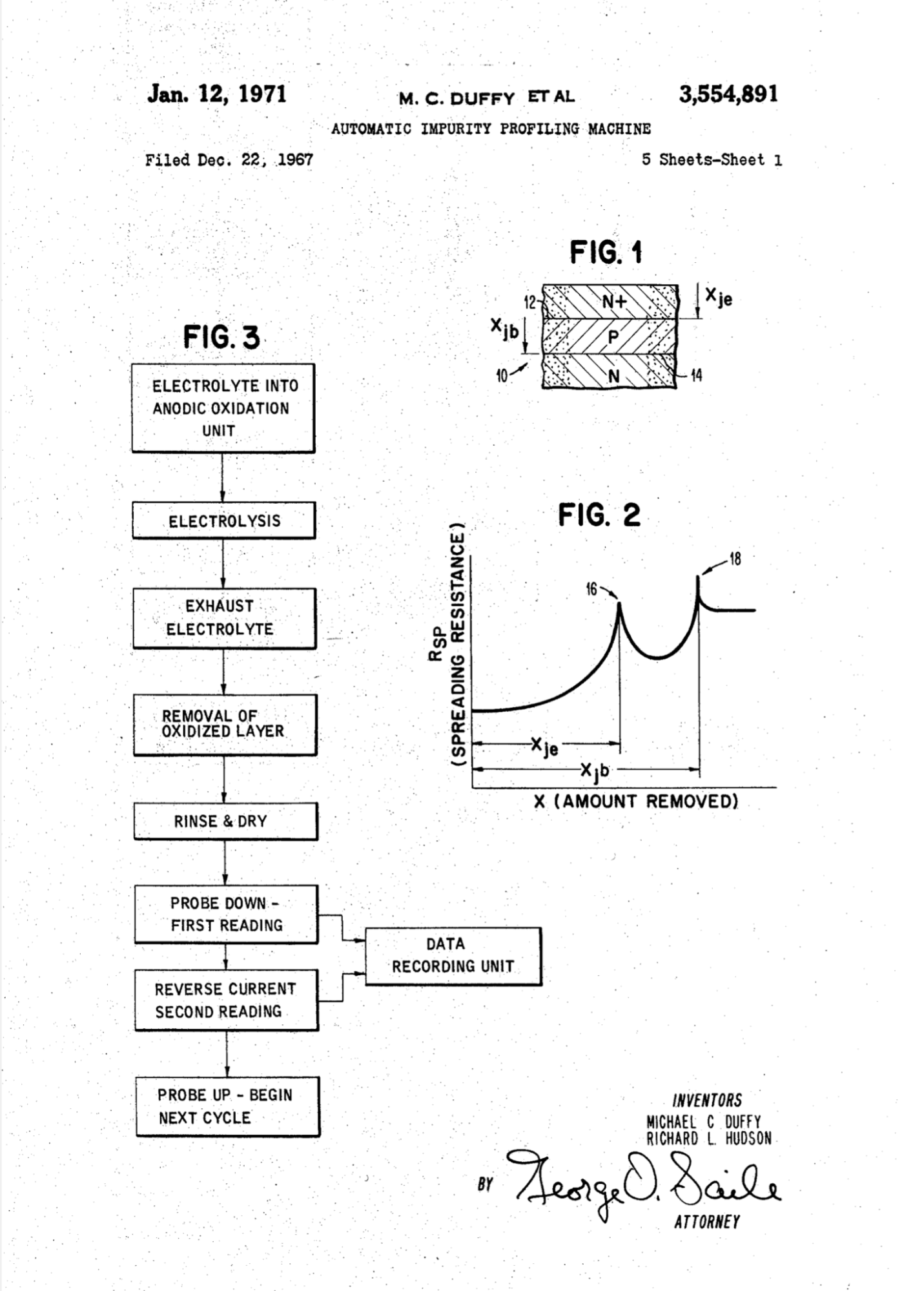

They transferred me again, out of that whole area in Poughkeepsie to East Fishkill into a different division altogether. This division was in an area whereby we were on the front end of developing these microchips for computers. Now, when I was going around trying to find out how to get this project done—discussing it with other people who had the technical expertise in the area—one particular fella, he was a Black fella, had a PhD in Chemistry. When I spoke to him, he said, “They’re setting you up, you know that, don’t you?”

I said, “No, I did not know that. But I’m glad you told me that because now I can’t fail. Because if I can’t get it done, I can always say nobody else could do it either.” So I had an excuse. In any case, what happened was that I worked on the project for six months and eventually I pushed a button on this little machine I developed and it worked the way I developed it. So I was very successful in completing the project.

A patent filing from January 12, 1971, assigned to Michael C. Duffy and Richard L. Hudson of IBM

IBM’s integration efforts also led to changes in the company’s famously paternalistic culture.

When I went into the company in ‘63, it was a very paternalistic company. It was the kind of thing that I knew was not going to last very long. Later on, this was confirmed to me by a woman that I knew. She’s white and had been there for about 30 years. She said that once Black people came into the company, it forced the company to change.

Let me give you an example of what I mean by paternalistic. If you were late to work, you were supposed to give your manager a reason for why you were late. If I’m late once every four months, I don’t think I have to give you a reason for being late. I don’t think I have to give you anything personal about my life or why I’m late. After IBM started hiring Black people, they changed the policy to say, OK, you have so many personal business days. If you have to take those days, you can. You don’t have to tell management anything.

My understanding initially was that it was a very paternalistic company. You could pick that up when you walked in. But after about maybe a year or two, they started changing their policies in response to how Black people had reacted. You have to remember, there’s a difference between what I’m going to discuss with a white person and what I would discuss with a Black person, especially at that time. So if you’re my manager and you’re white, there are things I’m not going to talk to you about, period. I don’t care how empathetic you think you are, there are things I’m not going to tell you. Don’t even ask me, and don’t ask me to lie, because I’m not going to lie—I’m just going to tell you that’s not your business. And so they had to change the policy in response to that level of distrust between the two groups.

After working on several technical teams, Dr. Hudson moved to Personnel where he gained insight into issues affecting his fellow workers. IBM was a “full employment” company, at least in theory: they claimed to never have layoffs, but in practice they would push employees out by asking managers to lower performance scores to justify letting people go. This involuntary attrition program disproportionately impacted minority employees, and became one of Dr. Hudson’s organizing priorities.

When I went to Personnel in 1970, there was a recession in the overall economy. And so I noticed people coming to me complaining about their appraisals. Now we’re talking about everybody, not just Black people, but white and Black complaining about their appraisals. Or their managers were telling them that they weren’t doing too well and needed to improve their performance.

I started to figure out very quickly that something else was going on. No one told me what it was, but I found out later that it was called the involuntary attrition program. Managers were being told that they had to get people out of the company by bringing their ratings down, then giving them a three-month performance plan and a six-week performance plan, and then kicking them out of the company.

I said, that is unfair, to make people think they’re failing when they’re not really failing at all. It had to do with the economy. You know it, I know it. But to make people…people believed something was really wrong with them. And it was just so heartbreaking.

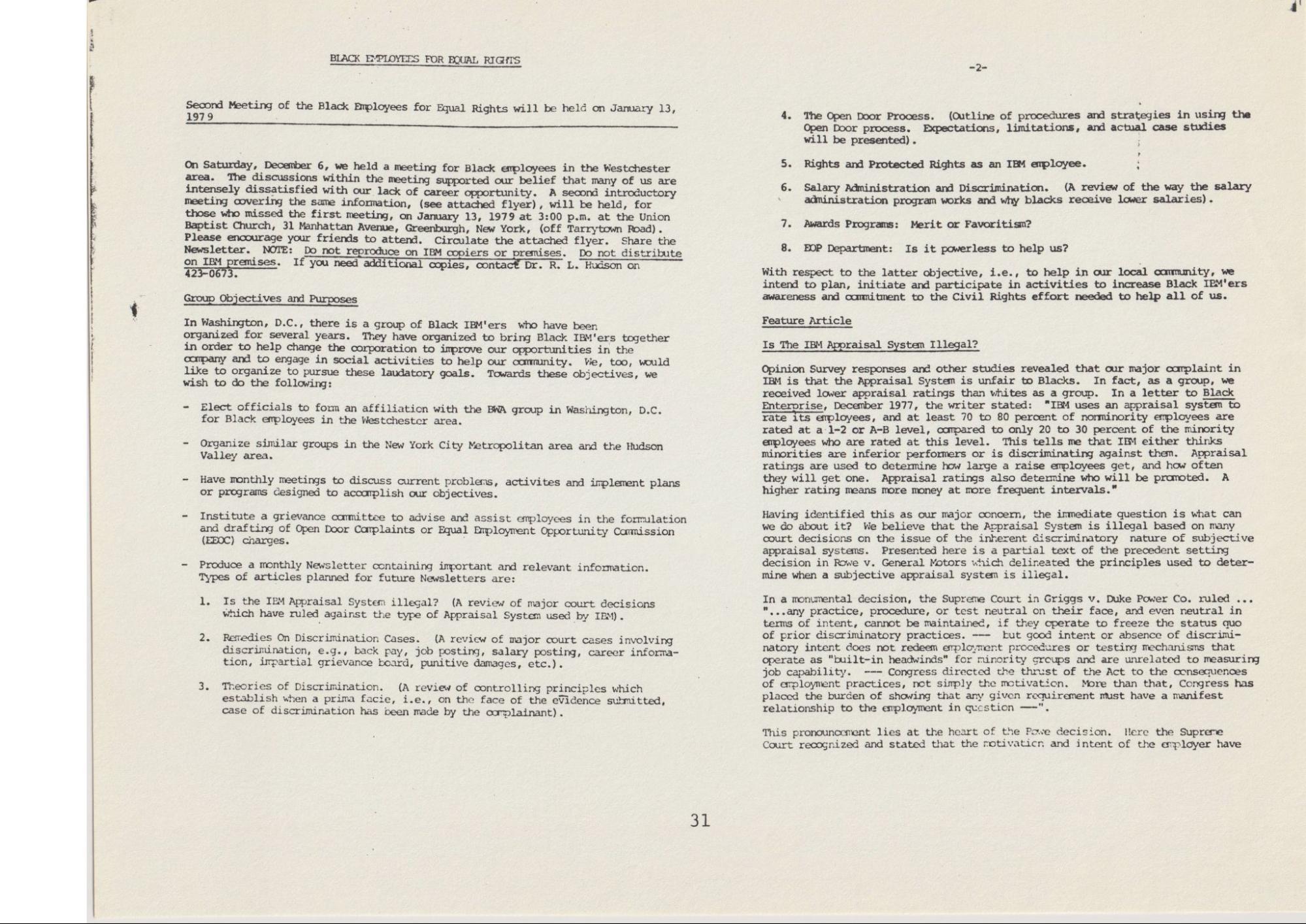

A page from the November/December 1979 edition of the newsletter, with details on the involuntary attrition program

In 1973, Dr. Hudson filed a complaint for discrimination with the NLRB. This brought him to the attention of the IBM Black Workers Alliance (BWA), formed in 1969 in Washington D.C, with the objective of organizing “to bring Black IBM’ers together in order to help change the corporation to improve our opportunities in the company and to engage in social activities to help our community” (BWA-NY Newsletter, Jan 1979). After connecting with the group, Dr. Hudson agreed to start a BWA-NY chapter and newsletter, which became a primary tool for recruitment, for informing workers of their rights, and for organizing efforts in other locations.

Most people would only come to me after they actually were threatened, or felt threatened. When they needed someone to help them out, then they would come to me. Prior to that, they would avoid me. But once someone got the newsletter and saw what was going on, a lot more would get together to try to organize, like for a department or a unit where they saw a lot of bad stuff going on that they were stuck in. Then they would try to get together. We’d have a group meeting where we would write up a group complaint and then file that with the chairman.

At some point, I had more people come in because of the newsletter. They would read the newsletter and say, we need to look into this as a group and do these kinds of things. But usually individuals would not come to me until they felt threatened about something. There was just a generalized fear that if you hung around with him, you may get fired. People noticed that. I’m sure that fear exists today in most jobs.

Another page from the newsletter

Dr. Hudson said of the BWA that they were explicitly not trying to form a union, though he described himself as a union man. I asked Dr. Hudson about why that was, and if there had ever been a discussion about forming a union.

I don’t ever recall having a debate about whether or not we should become a union. One reason why I would never try to do that is because I knew that I would not get support on that kind of issue, because the people I was dealing with quite often had degrees. And there was always this feeling that I wasn’t about to endanger my job trying to join a union. Because I knew that if I talked about unions, I probably would not have a job for very long.

One of the things I would often use as an example in my classroom about the so-called freedom of speech in America is to ask, “How many of you will go to your job and say, listen, we need a union?” What you find out is that just about everybody in the classroom, independent of age, will tell you, no, no, no, you don’t do that. Unless you already have a union. You keep your mouth shut. We’re living in a nation that’s been very effective at teaching people what you can and cannot do, what’s safe and what’s not safe to do. And talking about a union in a non-union company, that’s a sure way to get fired.

Once I understood something about the law, I understood that we did not have to have a union to try to make change within an organization. As long as you stay within the law, you’re relatively safe.

Dr. Hudson didn’t share the same fears as many of his coworkers around organizing and discussing unions. I asked him about his conviction and if he was ever concerned about retaliation.

I’m a product of the civil rights movement when all this unrest was going on in the nation. I was part of that generation. I could not participate like I wanted to, because I had to work and take care of my family—I couldn’t just go down south and do what I wanted to do.

But once I started working at the post office and then I started working at IBM, I discovered that things don’t change just because you got laws passed—you still got to do something beyond that point. Because discrimination is still going to occur. The system is still going to be set up.

Dr. Hudson has lessons to share with worker-organizers on examining and changing their workplace.

My advice to any employee is, number one, find out what the policies of that company are, so you can find out what rights you have as an employee that will be respected. Number two, find out what the grievance procedures are—if you have a grievance procedure–and how to use them to protect yourself. Number three, document everything. That’s to any employee, at any level. Document. If something is well documented at the time, it’ll come in useful later. I don’t care how good you think the company is. Things will happen.

Dr. Hudson reflects on his termination and the subsequent NLRB case, and explains that legal protections for workers rights are dependent on the political climate, highlighting the need for worker solidarity and self-organization.

So I got the [salary plan] and I decided to share it with a few other people. I told everybody to be there at the next [BWA] meeting in Washington D.C. because I’ve got something for them.

When I got down there, I had about 20 copies [of the salary plan] I had made up. I put it on the table and said, “That’s what you all want to see. I knew they’re not paying people right. You know that and I know that.” And they snatched it up.

You saw some very angry people in the room. Because we had number one and two performers not being paid in their proper quadrant.

Before I had passed the salary plan out, I had talked to the NLRB twice. Their lawyer said to me, “Since you didn’t steal this information, you have a right to use it.” So what I did is, I used it. And then [IBM] threatened me! So I took the letter down to the National Labor Relations Board and I filed a charge. [the NLRB] investigated, then filed a charge against [IBM].

Sure enough, when I went to work the next morning, they told me not to go to my work site, just to come into the office. I had been terminated.

If you read that case carefully, you’re going to find something kind of strange. I have a legislative right to do what I did. I don’t see anywhere in any legislature where IBM had a right to maintain confidential [salary] information of that nature. But the judge said, “Well, you have a right, and IBM has a right. I’m going to rule in favor of IBM’s right.”

At the same time, I got a call from a firm in Washington D.C. that was thinking about taking my case to the Supreme Court, but they decided against it because it was around the time of the air traffic controllers strike. It was a bad environment for this kind of stuff. So they said, we can’t take it now, because the courts are not looking at this [labor rights] stuff too favorably because of the air traffic controllers strike and what President Reagan had to do. So that takes care of that.

Despite everything, Dr. Hudson emphasized that he enjoyed his time at IBM and was proud of what he had accomplished with his fellow workers.

The company tried to recruit me to management, but I told them no. On two occasions. I said, no, no management for me. And I told them why. I said if I’m in management, I cannot do what I’m doing. If I make a commitment to go by your rules, you know, that’s what I’m buying into. I would not be able to do what I like doing best.

During all that period of time, I think it was a great career for myself. Contrary to what you may think, I really did not have a difficult time. Because when you know that you are doing the right thing … for example, when we were organizing in New York, some of the people in the group wanted to be very secretive about what we were doing. And I told them, no, no, no, no. All this stuff has got to be in the open. I don’t want people thinking that we’re doing something wrong. We’re following the law. We have a legal right to do this.

Next week, we will share excerpts from an oral history interview with Marceline Donaldson, a former salesperson in IBM’s Madison and Cincinnati offices between 1976-1979. Marceline worked to bring in the Pullman Porters to IBM and filed a discrimination suit with the NLRB. Though in different departments and cities, Marceline and Dr. Hudson’s stories share many similarities: they both talked about being attuned to problems on a systemic level, their deep commitment to justice and fairness, and their instinctive turn to organizing to improve their and other workers’ conditions.

Many thanks to Tamara Kneese, Danny Spitzberg, Wendy Liu, and the TWC Newsletter team for their help editing Dr. Hudson’s story.