Issue 8: A future worth planting for

07 Aug 2020

Roger Janus, an organizer with TWC Seattle, offers a hopeful perspective on how organizing may seem insignificant and arduous at times, but can achieve wins over the course of a multi-generational struggle. Meanwhile, tech worker organizing is on fire.

This kitchen appliance refuses to build tech for surveillance and warfare. Photo by Ari Laurel.

The Workers’ Perspective

By Roger Janus

A familiar cycle of my tech career is nearing its turnover: the shift back to work from a long period of unemployment. My work contracts have been short-term, either from the get-go, or ending abruptly due to a sudden lack of project funds. In these unstable cycles, I used to feel like a discarded leaf blowing in the wind, but now I’m closer to a maple tree seed, flitting from season to season to spur new growth where I land.

Granted, this cheery coping mindset can’t be chalked up to isolated self-improvement. As part of TWC Seattle’s TVC (Temps, Vendors, and Contractors) working group, we researched, discussed, and made a website that documented the historical context of our precarious work. Our engagement with the emotional impact this era of work has had on our generation, as covered in this essay by Plan C, has been immensely helpful to my mental well-being in the midst of a deeply unwell society.

Collective action just makes work less alienating. At my last onsite contractor role, some fellow employees and I were drawn together by common concerns with our company’s contracts with immigration enforcement. We began holding these issues up not to the review of special ethics “experts” hand-picked by the company, but to everyday coworkers across employment type, who were just beginning to lay the seeds of collective agency and dignity in our workplace. Our goal was to build a broader solidarity that would pressure the company into taking the lead of the workers on crucial issues, and time-tested approaches recommended drawing that strength from direct experiences. What stands out as I think back to that time is the erosion of what I then saw as a solid border between seemingly remote ethical concerns, and our immediate working conditions. It was in that spirit of breaking out of the “single issue” that we began to broaden ethics discussions to a whole host of topics.

I think about one Black coworker’s contribution. She described many incidents of unaddressed workplace racism, from managers as well as nonblack workers. A familiar story, her complaints would get lost in the wormhole of Human Resources, never to be heard from again. I think about the complete impotence of those who own and dictate our industries to undo the hierarchies of race that make our workplaces so hostile to Black lives. Why would they? Despite any hollow words or genuine intentions against, the foundation of their economic model rests on these forms of oppression. If their rule is genuinely threatened, they’ll rely more and more on the faux-rational James Damores of the world, invariably white male workers who benefit most from it, to maintain their vision of order.

When we began sounding the alarm about the immigration enforcement contract throughout the company, someone in my office block felt the balance of order disrupted enough to distribute their own cards directing employees to r/The_Donald. On the same utility poles where I taped posters for a solidarity campaign for fellow contractors who had just been retaliated against after collectively demanding better work conditions, neo-Nazi and and white supremacist groups like Identity Evropa have put up their own recruitment posters. Identity Evropa is now contributing greatly to the unofficial propaganda wing of white supremacist reaction, working alongside the official state-backed “fusion centers” to feed misinformation campaigns. Terroristic attacks on protestors have grown in frequency and force alongside these rumors.

There are also those who dress in progressive garb but clearly have no framework for solidarity, or eliminating the various oppressions that haunt us. In Angela Davis’ illuminating work on prison abolition, she describes a liberal women’s prison reformer who genuinely believes that equality means women’s wardens should be as heavily armed as men’s. That, as in men’s prisons, runaway prisoners should be shot at by guards rather than merely chased after. In this warped vision of equality, a lowering tide drops all boats. In this moment, I recalled how much more diverse my fellow contractors had been, as compared to my former full-time coworkers; how our bosses’ terms for diversifying employment come hand-in-hand with devaluation and destabilization of the work that new marginalized employees participate in, a well-studied but entrenched problem in many industries.

On an issue like immigration, senior leadership would talk a progressive talk on their value to American culture and economy. Some even have immigrant backgrounds themselves. But as we discovered, their effective practice was one of division and conquest via the classification of workers. Many of our direct and indirect coworkers did not have secure documentation: H1-B holders had to take greater precautions in organizing to avoid losing their visas in retaliation for speaking out.

I hope that the seeds we planted in my former workplace hold something in common with the seeds planted by the union members of the Martin Luther King Labor council, who in June voted to remove the Seattle police guild from their ranks. How many years, how many initial lunch break discussions did it take to build up the over 150 unions in that council? On Juneteenth, Angela Davis spoke at the Port of Oakland before the seed-planters of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, whose strikes closed down ports along the entire West Coast. Black lives were placed at a higher price than property that day, not just in words, but in deed. The dock workers’ collective act of defiance echoed through an already noisy Seattle, where Davis’ decades-long work struggling for the seemingly impossible idea of police abolition has suddenly entered the arena of political reality. The most regular demand of street protests for months now has been to defund the Seattle police by at least 50%, and reinvest in the community.

As I understand it, that sapling is continuing to grow from the seeds of solidarity we planted at those relatively small discussions and actions that year. It is being watered by us workers, who must take issues of workplace racism into our own hands, rather than waiting for those delayed, scripted responses trickling down from management. That we will live to see our saplings flourish into trees so unbending and well-tested that they could stop every server on the West Coast to defend the interests of life against the interests of property. Or even beyond that, re-purpose the tools of technology to serve the interest of life primarily, rather than the interests of property.

That might be a future worth re-planting myself for.

In The News

Protests for Black Lives Matter continue. Some march, others participate from afar. Some watch via social media, others watch via military drones and spy planes. VICE obtained police footage “in which people shine a laser at the plane from the ground. The plane locates those people, and within 20 minutes the suspects on the ground were surrounded by police.”

The US House Judiciary’s antitrust subcommittee held a day-long hearing on Big Tech, where the CEOs of Apple, Google, Facebook and Amazon testified. In his closing remarks, subcommittee chair David Cicilline made it clear that he believes that Big Tech has monopoly power: “Some need to be broken up, all need to be properly regulated and held accountable. This must end.” Following Jack Poulson’s report on how the US military uses China “as a cudgel” to make tech workers build weapons of war, a tech worker from Hong Kong tweeted: “Conservatives basically have 2 talking point in the tech hearing: 1. Fan the flames of nationalism and call Big Tech unpatriotic for working with China. 2. Argue that hate speech is free speech and how conservatives are being censored on tech platforms.” Professor and Algorithms of Oppression author Safiya Noble summarized Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony in a tweet: “we’ve invested billions of dollars in moderating hate speech… from the trillions we’ve made off of it.”

For more cringe from the hearing, watch Zuckerberg tell elected officials about his BBQ dinner. Bettter yet, consider signing this petition with 900k+ others calling Hawaii’s government to stop Zuckerberg from building a $100m mansion in Kauai.

Social media giants took baby steps to protect their users from dangerous misinformation. Facebook removed a Trump post that falsely claimed that children are “almost immune” to COVID-19, and Twitter suspended the Trump campaign account until it removed a tweet that made the same false claim. At the same time, Facebook fired an employee who was collecting evidence showing preferential treatment for right-wing misinformation.

Meanwhile, tech worker organizing is on fire. Members of TWC San Diego and 15 other groups followed the lead of sex workers, studied the EARN IT Act, and wrote an open letter calling on Senator Harris and Speaker Pelosi to reject the dangerous threat of surveillance. Tech Can [Do] Better, a community of Black tech workers, released Achieving Equity in Tech V1.0, which includes practical steps, examples of real change, and blueprints for employee organizing. Collective Actions in Tech published a guide to anti-racism employee organizing. Blizzard workers are demanding better pay and sick time, workers at midwestern tech giant Epic Systems are campaigning for a union, and 12 LGBTQIA interactive fiction writers at Voltage went on strike and won an average pay of 6.5 cents per word, a 66-94% increase.

In an act of solidarity, over 70 gig economy researchers signed an open letter advancing research principles to fight corporate influence over their work. The letter follows a flawed study by Cornell scholars who used Uber’s own data to conclude that drivers earned over $23 per hour, in stark contrast with another study that found earnings of just $9.73 per hour. Law professor Veena Dubal, one of the letter’s organizers, tells us that tech workers could also apply these principles to their own work:

The principles could also be used by tech workers working within these firms to guide internal decisions that impact the wages and working conditions of drivers. For example, software engineers could collectively demand that the drivers’ wages be algorithmically raised and standardized so that all time laboring is accounted.

After many months of rideshare companies ignoring California’s AB5 employment classification law, the state of California sued Uber and Lyft for wage theft. Erica Mighetto, a driver and organizer with grassroots group Rideshare Drivers United, started a running tweet thread posting people’s stories about delayed, deferred, wrongfully denied claims. She tells us:

With over 5,600 claims filed with the Labor Commissioner’s Office, I think we really shed some light on the issue of wage theft. I’m looking forward to seeing justice brought to drivers.

Meanwhile, the US economy continues to contract. US GDP fell 9.5% in the second quarter, the biggest drop on record. Devastatingly for working people and their families, the $600-per-week unemployment benefit dried up at the end of July. Mari Uyehara published “6 Jobless Workers. 6 Different Salary Levels. Zero End in Sight.”, which tells the stories of workers at different income levels. The lowest-earning worker in the story, a housekeeper who has lost $13,000 in wages, offers a harsh contrast to the highest-earner — a tech worker laid off from Airbnb who has lost over $150,000 in wages.

In History

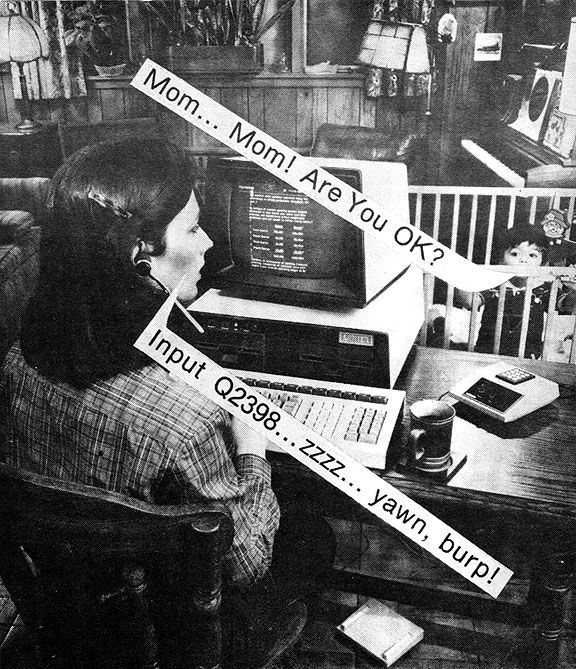

Sometimes, you are the appliance. From PW #4, 1982.

Tech work-life balance, at home. From PW #4, 1982.

Processed World was a zine that ran from 1981 to 2005 and published perspectives on everything from strikes at oil refineries to pickets at tech conferences.

In this personal reflection, Processed World founder Chris Carlsson, San Francisco-based writer, tour guide, and author of Hidden San Francisco: A Guide to Lost Landscapes, Unsung Heroes and Radical Histories, describes the zine’s origins, disputes, and contributions. Here’s an excerpt:

Our first issue came out in April 1981, with feature articles on the Blue Shield strike in northern California, and a survey of “New Information Technology” that tried to explore the ambiguous possibilities inherent in it. We saw ourselves as serious subversives, dedicated to fomenting revolution at the point of circulation, not production. By 1981 we could see that the deindustrialization process was leading to the much-touted service economy, but what were these so-called “services”? Mostly, as far as we could tell from our vantage points as temp workers in banks, accounting firms, real estate offices, and brokerages, it consisted of shuffling information—typing, mailing, filing, sorting, distributing, copying, and doing it all with then new-fangled skills like word processing on computers. We spent our days in front of green or amber monitors, worrying about radiation exposure from the electrons pouring though our Video Display Terminals into our faces.

Despite some disputes among Processed World writers, the magazine “was not conceived by missionary leftists, ‘professional revolutionaries’ who marched into the Financial District to educate the white-collar masses. Instead, a handful of people who had got into office work as one of the few ways open to them to make a living, got fed up with their isolation and with the silence around them concerning all the important questions. They [we] set out to produce a vehicle of communication for others working in financial districts with similar attitudes to their jobs and the world at large.” So wrote Adam Cornford under his pseudonym of Louis Michaelson in an exchange in PW #6.

After the first issue came out, we were deluged with letters to the editor and new volunteers. We had struck a chord. But beyond being dissident office workers in favor of overthrowing wage-labor, what were we going to do? We kept writing about our situations, and invited “tales of toil” from our readers, which poured in as both letters and articles, and filled our pages for the rest of the 1980s.

Here’s to more meaningful tales of toil, organizing, and joy.

Processed Worlders at the Office Automation Conference at the Moscone Convention Center in San Francisco. From PW #5, 1982.

In Song

Song 33 by Noname

They’re talkin’ abolishin’ the police

And this the new world order

We democratizin’ Amazon, we burn down borders

This a new vanguard, this a new vanguard

I’m the new vanguard