Issue 10: Wages of Short-Lived Startups

04 Sep 2020

After eight grueling years stitching together a design career, Vikram Rojo shares how bonds with friends and family, plus ad-hoc tweets, helped him break into and break free from a string of startups and their bureaucratic traps. He considers himself lucky, and demands the real question: how might we as tech workers demand more than pay, but dignity? How can we all get a decent job, a home, and a chance to get by?

Meanwhile, in the news, landlords are using data to enable evictions, but workers are showing how innovation and demands go together. And in history, some lesser-known and politically powerful pages of Black Panther comics.

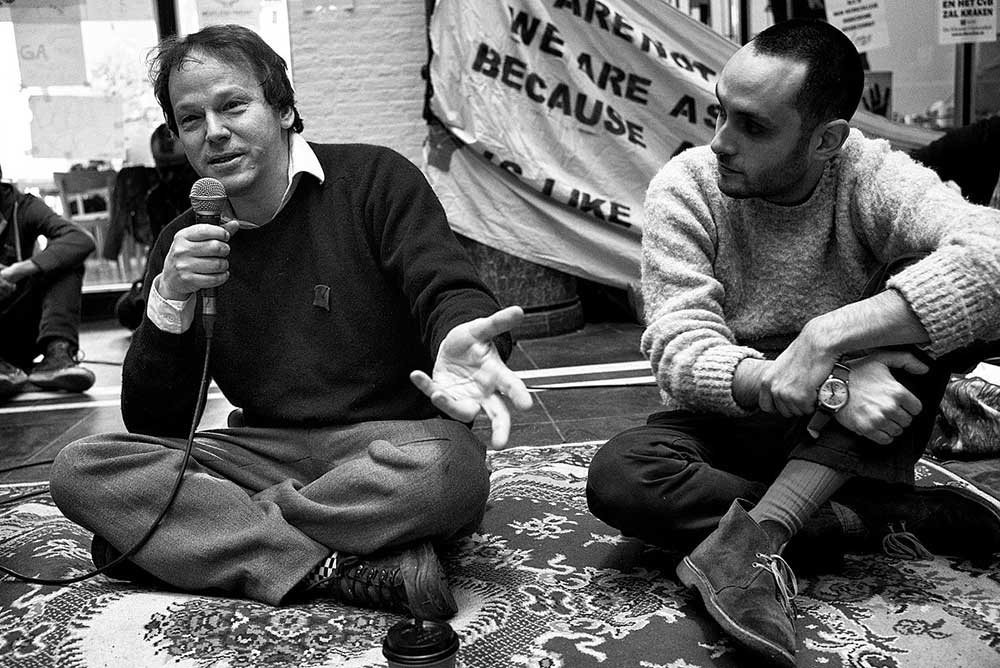

Rest in Power David Graeber (1961-2020), who constantly asked us to challenge the stories we tell ourselves about human nature. / Source

The Workers’ Perspective

By Vikram Rojo

After years of being undocumented plus stints of minimum-wage service jobs and underpaid agency work, my first tech job in San Francisco felt miraculous. I’d flown from Michigan to San Francisco with just a backpack to attend a conference. During the first talk, I spotted a familiar face in the crowd. We hugged with a fondness reserved for internet friends and by lunch they’d introduced me to another friend. And so, within 24 hours of landing in San Francisco, I had an offer for double my Midwestern salary as a web developer. Not long after returning to Michigan, I loaded all of my belongings aboard Amtrak Express.

The job would only last 10 months, an arc from a high point of a celebrated funding round and office expansion to an almost predictable downsizing in a new office that was already half empty. That set the pace for my next eight years, as my career meandered through mostly failed or dying startups. But given where I started, I’ve been content to observe the bureaucratic life of tech as a bystander. For years I felt guilt for earning what I did relative to friends and partners, and grudgingly satisfied with whatever was handed out. I never negotiated an offer, fought for a promotion or challenged the terms of a layoff. Especially in this moment of universal suffering, I feel content to just have a job.

If there’s a monolithic tech worker, I haven’t met many. I can count on one hand the number of folks that have netted over a quarter million dollars from shares. Many of them felt cheated out of greater ownership. And yet, we subscribe to the image of a white or Asian male tech worker who makes upwards of $200k, has had successful unicorn exits, benefits from an influential network, and is simply waiting to start their own company with oversubscribed investors. So with each new job, I tell myself that these promissory shares will afford me my dreams. But I’ve yet to exercise a single share from any of the startups I’ve worked at. My reasons for not purchasing shares varied: I didn’t hit the one-year cliff; I saw decline in value coming; or I simply couldn’t afford it, between the strike price and tax hit. I’ve seen friends regret buying paper money with real savings, and I’ve seen others lose out on vesting because their family couldn’t afford the lack of liquidity. You just can’t beat the market, and worse, the startup market is volatile.

At almost 40, I realize that majority of us tech workers look nothing like what we aspire to: holding shares in a steadily growing company with a path to exit and a home. But, I feel like I’ve finally reached that: for the first time in my life, I was insured for a whole year. A few years ago, I reckoned that I’d have been better off if I had gone to work for a public company. A job with a few thousand shares of stock in a monoloith like Microsoft go a lot further on the NYSE than in the cap table of a Series A startup.

Now, coming up on my eighth year working for startups, what do I have to show for my pockmarked resume at a string of startups that have faded into obscurity? Beyond cynicism for the tech worker social contract and a network of equally cynical peers, I finally landed a six-figure salary. My current company is doing well; it’s even possible that we’ll cross the valley of hypergrowth to an IPO. Still, repeated experiences of watching leadership teams commit to unachievable goals and failing dismally has me looking over my shoulder.

I don’t think it’s asking too much that I earn a decent salary, have job stability, keep reasonable hours, have autonomy in my work, and feel that I can shape the direction and values of my company. Startup employees are often lured in with the promise that they’ll own stock in the company, but owning 0.05% of a company when the CEO owns 30% is far from co-ownership. In practice, startups are rarely the egalitarian dream their founders present them to be. Many tech workers, myself included, would rather be baking bread.

I love to ridicule corporate life, but I’ve come to see it as one of the few social institutions that remains intact. Gone are churches, bingo halls, multigenerational families and lodges. This vacuum of cohesion leaves belonging almost entirely to brands, corporations and media. But only one can feed and shelter you. In a fragmented society, startups have sometimes given me a sense of belonging, but at other times, a profound alienation. After all, even in the most seemingly stable companies, things get messy: despite massive stock gains, there have been massive job cuts in this sector. It makes me question the fragility of corporate institutions and whether this is the community I want to belong to. I’ve seen coworkers agitate for transparency and accountability, but it’s challenging. Leadership and business outlook can quickly change, it’s hard to speak out alone, and organizing sometimes just feels like extra work.

A while back, a coworker of mine got laid off. They didn’t get along with their manager, which is usually a job-killer. It was a months-long ordeal, particularly because the manager had already been reported as abusive. Yet they were laid off a month shy of their vesting cliff. That was the beginning of their ordeal. They were suffering multiple crises and the promise of normality at work kept them going. Now they were on the ledge of a rooftop. We spoke for hours that night and many nights following. There was little I could do; bureaucracies are built to be blameless.

Retaliation is hard to challenge. I know this because my mother was wrongfully terminated eight months before her retirement after a dozen years of service. Women of color and disabled workers are easy targets for bad managers. My mother went to court and settled for a pittance. There’s a chart flying around Twitter about wage theft taking more than $35 billion from employees, but what happened to my mother and my friend also robbed them of their dignity and belonging.

The pandemic is changing the nature of work, in ways that are better for some of us but deadly for others. Corporations are reevaluating the worth of workers, and the most common outcomes include layoffs, withholding hazard pay, and providing substandard protective equipment. For a lucky few, there’s a silver lining: it’s the perfect time to move away and go remote. Others have no choice but to stay and suffer. I’m grateful that I was able to move to Colorado a year ago while keeping my job; today, many are contemplating similar moves, and I’ve found myself counseling others on how to negotiate the request. There are conversations happening now that were unwelcome years ago, in spaces that are far less hostile to worker concerns.

It’s far from certain that the future of tech labor will be comfortable. Design history suggests the opposite: after all, there was a time when operating a printing press was a professional job. I’ve watched out for dead-ends in my career, but I can’t say what no-code or machine learning will bring. I’d prefer instead that we agitate for greater access to the industry, for more collective ownership over what we produce, for more control over how our labor is used, and for a stronger security net than two weeks’ severance.

In The News

First, some news from us: we’re announcing an open call for submissions.

As tech workers organize and build power in the industry, we invite you to share your workers’ perspectives — even if it’s just an idea. We also welcome suggestions for tech labor news, historical events to highlight, song recommendations, and other contributions. Read more here!

Now, news from tech and labor.

After police in Kenosha, Wisconsin brutally and wrongly shot Jacob Blake, a Black man, the WNBA inspired a wildcat strike with dozens of sports teams withholding their labor. Sports livestreaming is a massive source of ad revenue, and social media is amplifying pro athletes ‘now more than ever’ under COVID-19. What made a difference was, players settled on a demand, albeit less than what justice requires: use stadiums as polling stations in the November general election. And, they won.

A 17 year-old white supremacist murdered two people who were protesting the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha. He was enabled and encouraged in part by militias organizing on Facebook. In response to CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s fumbling in the face of calls to stop the hate speech and violence, Facebook employees spoke up — as they have time and again. And despite Zuckerberg’s statements that his company took down a Facebook event where people discussed gathering in Kenosha to shoot and kill protesters, the company never removed it.

As nationalism and Islamophobia deepen in India, Facebook employees are also upset with how the company refuses to take down anti-Muslim bigotry. One Facebook moderator told us that with 35,000 moderators and millions of decisions made each day, it’s a thicket of wicked problems:

“You need to write rules for them to follow, guidelines, whatever you call them, so that everyone treats the same content in the same way… One of the problems at FB is that they require moderators to maintain 98% accuracy, which is not realistic and creates a culture of management by numbers. Moderators are dehumanized and stressed by it.”

Tech policy analyst Divij Joshi clarified Facebook’s legal status in India in a thread, adding “TL;DR — The updated FB ToS does not change the legal reality (vacuum rather) under which content moderation exists in India (and to my knowledge, in the rest of the world).” But, while employees are asking Zuckerberg tough questions at company all-hands meetings, it hasn’t worked — yet.

For many of us, the flip side of work is paying rent. Abigail Higgins and Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò wrote about how police and landlords collaborate to evict tenants — with help from private surveillance. Specifically, authorities buy their data to conduct “automated background checks” on tenants, move eviction court proceedings without an in-person hearing, and trap people in a “circle of dispossession”. The LA Tenants Union built rapid-response phone and SMS tool to create “a base of empowered tenants who can educate and support each other in times of need,” but we need more proactive organizing and tech. Even in the midst of a global crisis, landlords aren’t hesitating to evict our friends and neighbors, and joining a tenants union is a crucial step in building the power to resist.

We believe worker demands and innovation go well together:

- In solidarity with the Muslim Justice League’s demand to get the BRIC Fusion Center out of Boston, the Boston Tech Worker Organizing Group and TWC Boston started a pledge you can sign: #NoCodeforCops.

- As a critical alternative to police, the Anti Police-Terror Project launched MH First, a phone line for mental health first-responders.

- Armin Samii, a programmer turned Uber Eats delivery driver based in Pittsburgh, created a browser extension that shows when Uber underpays by distance.

- While California wildfires create the worst air quality in the world, the Gig Workers Collective is demanding Instacart cease operations and provide disaster relief.

- Amazon protestors demanding higher wages built one of the most innovative devices in history — a guillotine — right in front of Jeff Bezos’ mansion. Elsewhere, in front of the San Leandro Amazon distribution center, a car caravan formed a blockade while playing The Coup’s song “5 Million Ways To Kill A CEO.”

- Outside of distribution centers near Chicago, Amazon workers hang cell phones from trees to get a millisecond advantage over peers trying to claim jobs. Amazon probably knew that before most, with their sophisticated spy program surveilling workers in private Facebook groups. And as the company claimed to suspend it in a call to the reporter who broke the story about their spying, Amazon is hiring analysts with explicit union-busting duties.

- Finally, our demands need to be about life, not work. As one tech subculture scholar tweeted, “the tech industry ruined being passionate about things… if you tell me you are passionate about something there’s a 90% you work in tech and the thing you’re passionate about is a salesforce customization.” Don’t be that person.

In History

The true beauty of Black Panther isn’t utopian technology, but political vision – and a huge, little-known volume of that never made it from comic book pages to screen.

Like all media empires, comic books have a way of leaving ideas out as they turn into films. Chadwick Boseman, the actor who played King T’Challa in the Disney film, passed away. He will be appreciated for a life of achievements, from his days at Howard University where he and other organizers confronted the president to stop arts education cuts, to 2018 when students spontaneously celebrated going to see Black Panther in theaters. But, despite what he stood for and how he lived, Boseman’s portrayal of T’Challa was filtered through a Disney lens. Black Panther director Ryan Coogler, whose first film Fruitvale Station told the story of police murdering Oscar Grant in cold blood, met with a range of former Black Panther writers in the brainstorming phase — including with Reggie Hudlin and Ta-Nehisi Coates creating other characters.

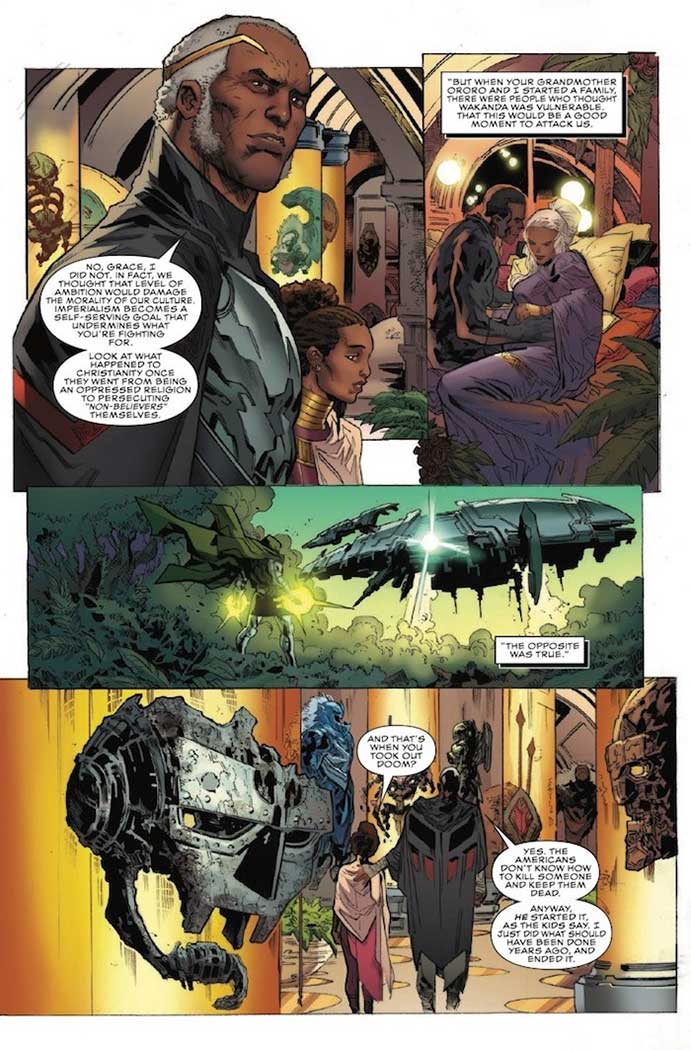

Duane Deterville, a visual culture scholar in the Africana Studies Department at San Francisco State University who teaches “Black On-Line: Cyberspace, Culture, and Community,” highlights just how important these other storylines were. He points us to one Hudlin comic where T’Challa, a grey-haired elder and world leader, tells his granddaughter the cautionary tale of American empire:

“…we thought that level of ambition would damage the morality of our culture. Imperialism becomes a self-serving goal that undermines what you’re fighting for. Look what happened to Christianity once they went from being an oppressed religion to persecuting ‘non-believers’ themselves.”

A page from Reggie Hudlin's Black Panther, all rights reserved. / Source

Comic books are far from perfect, as we learned from David Graeber, anthropologist, anarchist, and writer on debt, jobs, and bureaucracy, also passed away recently. We’re grateful for his essay Super Position, in which Graeber discusses how superheroes live in and maintain an “inherently fascist space” of counter-revolutionary violence:

The supervillains and evil masterminds, when they are not merely indulging in random acts of terror, are always scheming of imposing a New World Order of some kind or another. Surely, if Red Skull, Kang the Conqueror, or Doctor Doom ever did succeed in taking over the planet, there would be lots of new laws created very quickly, although their creator would doubtless not himself feel bound by them. Superheroes resist this logic. They do not wish to conquer the world—if only because they are not monomaniacal or insane. As a result, they remain parasitical off the villains in the same way that police remain parasitical off criminals: without them, they’d have no reason to exist. They remain defenders of a legal and political system which itself seems to have come out of nowhere, and which, however faulty or degraded, must be defended, because the only alternative is so much worse.

This perspective matters because, in lesser-known comics left out of the Disney universe, the Black Panther breaks the mold; he fights fascism as a system. An essay in Polygon says the Black Panther “predates the October 1966 founding of the Black Panther Party, the socialist and anti-fascist group that organized to unite African-Americans against police brutality and racial supremacy in American society and politics,” but it is easy to believe otherwise; in another page from Hudlin, the narrator says, “Cap [Captain America] didn’t know the Wakandans had already beheaded the Nazis days ago.” Cap then tries to fight Black Panther in hand-to-hand combat, and loses, before eventually trying to help. But as T’Challa tells his granddaughter: “Americans don’t know how to kill someone and keep them dead.” That someone is a reference to Dr Doom, a villain of Romani descent and therefore an enemy of Red Skull, another villain who built mechanized suits and other weapons for the Nazi regime. Black Panther fought them all – and their empires. Black Panther had vision, one we must keep alive for the future.

In Song

Fight Like Ida B & Marsha P, by Ric Wilson

I got bodily autonomy

And its policy is people over property

Treat us like pieces of monopoly

One day you’ll be nothing but the rich to eat

Uh, Defund the police

Abolish the prisons, or don’t speak a word to me

Stop ICE and let ‘em all free