Issue 13: Don't let Uber get away with it

30 Oct 2020

Welcome back. In this issue, former Uber engineer Eddy Hernandez shares his story about the company’s in-house army pushing Prop 22, and how office workers are being coerced to support it just like their coworkers, the drivers. We stand with all workers organizing against Prop 22, an attempt by Uber and other gig companies to cut rideshare and delivery drivers out of established labor protections. And beyond Prop 22, we cover new research on tech company tax dodging, racist surveillance and political censorship, music streaming workers demanding fair pay, and an app selling gig workers a place to pee.

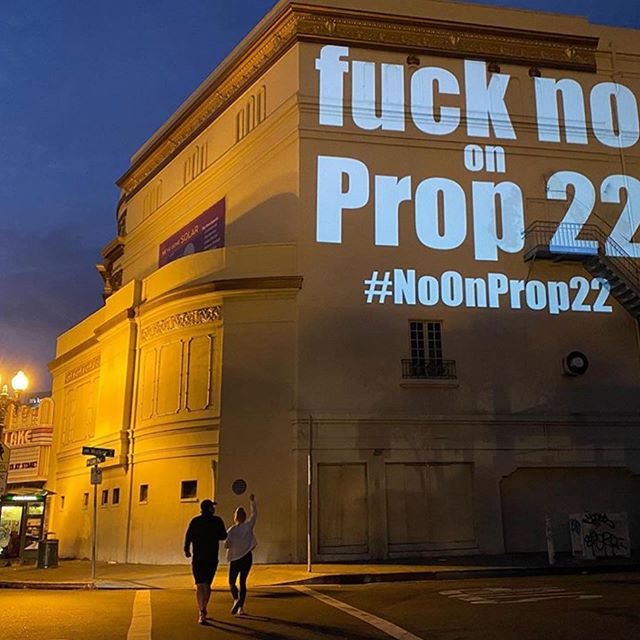

Fuck No on Prop 22. Image by Boots Riley. / Source

The Worker’s Perspective

By Eddy Hernandez

Growing up, I worried a lot about money. I remember reading the classifieds as an early teen, checking the minimum age requirements for jobs as if one of them might be below the Texas Child Labor law requirements. As soon as I was able to work, I did. I worked for restaurants, caterers, and contract jobs my parents would take. With my Dad, it was odd jobs like laying tile, making vinyl signs, and doing lawn care. With my Mom, it was a weekend every now and then giving out free food samples at Walmart. It always took so long to get paid for those jobs that by the time I did get paid, it was a nice little surprise. Regardless of whatever job I was working, I usually split half my paycheck with my parents. This is my background and what I carry with me.

When I graduated from college, I figured tech would be a career path that would make it easier to pay off my student loans, help my family out and have some sense of financial stability. So, like so many others, I came to San Francisco seven years ago with a dream that I could find better, well-compensated opportunities. That was the appeal of big tech for me.

About a decade into my journey in tech, I had made it. I joined Uber in February of 2019 as a Senior Software Engineer in Engineering Security. I joined despite knowing the history of the company: during the interview process, I was convinced of Uber’s path to rehabilitation due to leadership changes as well as improvements to their performance review process. I believed that Uber was forced to change, not because they wanted to, but because they had to if they wanted to keep making money. I also felt hopeful knowing that there was a Diversity and Inclusion (D&I) team and an Employee Resource Group (ERG) that aligned with my identity. They frowned on me using “Latinx,” which was a small red flag for me, but I was grateful to have access to resources that I normally wouldn’t have given my background, and I thought I could use my position to advocate for better conditions for drivers. I went in believing that drivers deserved more: it was the drivers who moved people, who delivered value to customers. Without the drivers, Uber was nothing.

I spent months heads-down attempting to find my ground. As I settled into this new space, I started to check in with my coworkers’ sentiments around paying drivers more. A majority of responses were along the lines of “that wouldn’t work.” “The business model doesn’t support that.” It wasn’t a flat-out “No,” but I was surprised. The company prided itself on hiring the most talented folks out there to solve really tough, complex problems, but when it came to paying drivers more, everyone was stumped.

During company-wide discussions like all-hands meetings and D&I and ERG office hours, I often wondered out loud, “What about our drivers?” Given the realities of COVID, what could Uber do better for drivers? Before COVID, driving for Uber was already a dangerous job — drivers always faced the risks of traffic accidents and assault — and the pandemic added a new dimension of danger. While we were safe behind our computers with a living wage, health insurance, unlimited PTO, stock, and work-from-home stipends, what perils were we sending our drivers out into without these benefits? Shouldn’t we at least be providing hazard pay?

The general consensus was that we were doing enough. One employee, who used to be a driver, was OK with the situation because at least people had the option of working. I struggled to find the words to explain why I thought we needed compassion for drivers who were getting paid less to do more. The way we were expected to depersonalize drivers when we discussed them certainly didn’t help.

At the same time, Uber was pushing forward a multi-million dollar campaign behind Prop 22, a selfish attempt to buy policy change that undermined the democratic process. Although Uber claimed that people overwhelmingly supported the proposition, it seemed to me that some of that support was manufactured by the campaign’s massive outspending compared to Prop 22’s opponents. (As of writing this, the pro-Prop 22 campaign had raised over $200 million, with $61 million coming from Uber; Prop 22 opponents had raised $19 million, mainly from organized labor.)

Inside the company, pushing back against Prop 22 was like trying to stop a bullet. Leadership made it a company-wide initiative, which meant that Prop 22 was part of employees’ performance and promotion reviews. How well did you execute on Yes on Prop 22? UX writers, designers, developers, marketing and policy folks were expected to aim all their efforts at getting a Yes on Prop 22. On top of that, internal messaging communicated an expectation of loyalty toward Uber above all else. Unlike drivers, I did not have to deal with constant in-app pop-ups asking me to commit myself to voting Yes on Prop 22. But if I as an engineer with considerable power, influence, and access to Uber leadership felt coerced into silence about Prop 22, how did drivers feel?

I decided to resign. It was a Monday morning, and my to-do list had just one item: resign. I printed out my resignation letter and held it in my hands when I gave my notice. During my last two weeks, I spent time in Slack pointing folks to things like the ACLU and NELP’s legal response to Prop 22. I shared that police unions, the worst unions, were backing Prop 22. I also shared that I was leaving.

People reached out to me to talk. Why leave? What was I was going to do? What could they do to help? I had nothing lined up. My answer surprised them, with my manager remarking that he had never met someone like me, who was willing to walk away when a company’s direction wasn’t aligned with their values, despite being in the industry for decades. I couldn’t help but wonder what that said of the industry we’re in. A few weeks later, I read an op-ed by Uber engineer and former driver Kurt Nelson about voting against Prop 22, and felt a load lifted off my chest.

I had coworkers make their case for co-opting the #DeleteUber hashtag for their Black Lives Matter billboards, and then shut me down in conversation when I asked about what we’re doing for Black drivers. It was pure marketing. Uber, like other so-called sharing economy companies backing Prop 22, dehumanizes the working class with its parasitic business model, dehumanizes drivers and couriers, and even dehumanizes its own corporate employees, particularly BIPOC employees, by touting their volunteers’ D&I work as their own without giving much to those communities in return.

The companies are pushing Prop 22 in their most egregious effort yet to divide classes of people associated with the company, but it’s not just about Prop 22. Companies like Uber are a spawn of late-stage capitalism. They have no compunction about dropping formerly valued employees if it means a larger profit margin, because their business model is rotten to the core. That’s part of the reason people I asked couldn’t figure out how to pay drivers more, or didn’t want to. Today, Uber is trying to keep drivers from organizing. Tomorrow, it might be the rest of us.

Prop 22 is Uber and other companies making a last-ditch effort at cementing a system that centers the exploitation of the people who bring value to the company. Don’t let them get away with it.

In The News

Trickle-Down Economics

Last issue, we devoted the entire news section to No on Prop 22, gig companies’ $200m+ attempt to buy legislation. This week, drivers sued Uber over the barrage of in-app ads, political coercion, and misleading claims about Prop 22 for up to $260m in penalties. Also, there’s a new app helping gig workers find a place to pee. Unless you believe peeing should be a luxury, vote No on Prop 22.

As part of the new-normal work-from-anywhere tech culture, Reddit announced that they will permanently offer work from home, and will offer San Francisco or NYC-level salaries no matter where the employee is located. In contrast, UMAW, a group mobilizing music workers, launched Spotify Justice to demand that the dominant streaming platform compensate hard-hit workers during the pandemic. And Jeff Bezos has decided he will not end world hunger today.

Tech, Death, and Taxes

Former Google research scientist Jack Poulson published “Death and Taxes,” an analysis of tax evasion by 57 tech and defense companies. Pulling data from thousands of SEC filings, the report shows how highly profitable companies like Nvidia have an effective tax rate of 3-5%, and how Facebook, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft (FAAAM) appear to be the biggest winners of Trump’s corporate welfare, saving $37B every year, in addition to the billions they are allowed to avoid provisioning. Şerife Wong called the report “a treasure trove for journalists and researchers on Silicon Valley.”

Jack told us that “part of the reason tech companies have so much public policy influence is that they are starving the beast by depriving the public sector of their tax contributions and demanding fealty as part of funding the nonprofit sector.” His report points to Google suppressing anti-monopoly critique at New America Foundation, Amazon becoming the biggest donor on climate issues, and Microsoft writing a facial recognition bill. With big tech starving the public sector, it might be time to update their acronym to FAAAMN.

Who Suveils the Surveillers?

A sales director at surveillance startup Verkada abused camera access to capture photos and make sexually explicit jokes about women collegues in a Slack channel. Is this tech-enabled harassment what people talk about when they talk about The Future of Work?

Students are fighting back against invasive proctoring surveillance citing data leaks, privacy concerns, medical conditions and access to technology. Forget comfort tech, try criminalization instead. A student who gave the name Bea decribed being subjected to unwarranted stress:

“On one occasion, I was ‘flagged’ for movement and obscuring my eyes. I have trichotillomania triggered by my anxiety, which is why my hand was near my face.”

Twitter partner Dataminr, which markets itself as an AI platform, appears to be human-sorted, carrying with it the usual human biases. Employees suggest that the public sector crime service amplifies racial and cultural biases while targeting minors. Dataminr’s PR firm insists that monitoring the speech and activities of people without their knowledge is not surveillance.

There is at least one known good use of surveillance: tracking abuses of power. Activists built a facial recognition tool to identify police officers, and law enforcement is not happy about it.

Shipping Censorship

Facebook would definetly not like it if you installed NYU’s data tracking tool, Ad Observer. Facebook, one of the largest collectors of user data, sent a cease and desist order to NYU Ad Observatory, a group collecting data on tech companies.

Not to be outdone, Zoom censored a Zoom event on censorship which it claims was done in response to a request by lobby groups.

Dorsey, Twitter’s mostly-absentee CEO, was not involved in the decision to block Twitter users from sharing controversial news about Joe Biden’s son, and this is part of his “hands-off style”, which lets him “pursue his passions.”

Caste, Creed, and Conspiracies

Since a lawsuit against Cisco for caste discrimination emerged, Equality Labs has registered hundreds of similar complaints from workers at Facebook, Cisco, Google, Microsoft, IBM, Amazon, Apple and more. 30 female engineers released a statement.

Facebook’s top India executive leaves after allegations that she interfered with how the company enforces its hate-speech policy to benefit India’s ruling party.

According to a recent study, Facebook’s opaque algorithms are 5X more polarizing for conservative users than liberal ones. Further, Facebook was found manipulating promoted news to appease conservative outlets while throttling liberal and progressive outlets, costing them hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue.

In History

While engineers in the US have earned a reputation for putting career ahead of worker power, we know this isn’t always the case: in Italy and France during the 60’s and 70’s, it was quite the opposite: engineers organized in the face of hostile managers and peers, too.

The following is an excerpt from Radical Tech Workers of the 1960s and 1970s: Lessons from France, Italy, and the US for Organizing in Tech Today, an article for Science for the People by Christine Andrews and R.K. Upadhya (who also wrote the worker’s perspective in issue 4, “Leaving the Bubble for Texas”):

The first visible round of this new militancy was in early 1968, at Sit Siemens, a large telecommunications firm. The labor force was highly stratified, featuring a large pool of female assembly-line workers, as well as many technicians and clerical workers. Grievances, even among the less privileged, were less about wages and more about the associated health concerns and required speed and intensity of the work. Therefore, when major strikes began breaking out, a large minority of white-collar workers joined in, even though they had largely been excluded from the process of drafting demands. This new dynamic was a stark contrast to the fierce divisions between blue- and white-collar workers in other industries like automobile manufacturing, where office workers were largely opposed to the strikes, and thus attracted much hostility from the strikers.

This phenomenon spread as the year continued. At Borletti, an appliance factory, a growing movement of white-collar militants made strong efforts to rectify their past stances of buying into their ambiguous middle-class status and opposing protests by the blue-collar workers. This turn was not the result of some new-found altruism; it was a response to the failure of a white-collar strike in the winter of 1968, which the blue-collar workers had not supported. The incident demonstrated to workers, at Borletti and beyond, that serious progress could be made only if real solidarity was built between different strata of workers.

…

Professionalism continues to be a key problem today, with computer science departments, tech companies, and tech-related communities all centering ideas of individual achievement, entrepreneurship, and the wisdom of the tech bosses. A 1974 SftP article, “Pushing Professionalism [or] Programming the Programmer,” lays out the consequences of failing to confront this ideology all too presciently:

The critical question now is how will programmers resolve the emerging contradiction between their self-interest and management’s desire to facilitate a self-regulated workforce of programmers. Will the resolution take the form of passive acceptance of management’s version of “professionalism” while working conditions, hours and wages deteriorate? Will it take the form of a narrow trade unionism which calls itself professionalism but which seeks to defend the remaining special privileges of programmers to the detriment of other workers? Or will programmers begin to identify their self-interests in common cause with other workers who confront the same management–the secretaries, keypunch operators, janitors, machine operators, and production workers? The latter course of joining with other workers will occur only if politically conscious programmers actively struggle for it; otherwise some form of management-inspired professionalism is the only alternative. Although less virulant [sic] than sexism or racism, a professionalism which grants special privileges and status to a few skilled workers is one more weapon in management’s arsenal of divide and conquer.

Despite these obstacles to labor organizing in tech, Pete Barrer and Larry Garner identify potential grievances that could motivate even the most privileged and professionalized workers. For defense engineers, declining work stability and deteriorating conditions in the field are identified as potential inroads for organizing. In addition, engineers were increasingly frustrated with work that they viewed as meaningless.

We as software developers and rideshare drivers can support one another more than managers, lobbyists, and other higher-ups with conflictings interests. If you feel your career or professional identity start to pull you away from your coworkers, stop. Get help. Talk to a coworker about your working conditions and how it got this way, today.

In Song

The Formula - At All Cost

Let me set the formula for a utopia, shattered dreams and bourgeoisie schemes leave classes to up-rise

Take a theory raise awareness, class-consciousness, then arm for the coup d’etat, strikes, and for the resistance

Don’t let your fears stray the goal

The present is not what we perceived it to be, current culture will not thrive through this time

Release me from this binding exponential downward spiral

Everything we say we need serves to lock us in

Praise leader’s words, then return to the fight, and the strikes, until you have won it all

Then rebuild by learning from previous mistakes, keep history close to your heart and your mind

And never forget to stand against all opposition, and base a society from this one thing, it’s…

Freedom

Raise a voice for a change, stay up way up, for your own cause, it’s better now than never so