My crew and I walked off a set

19 Oct 2021

Today we hear from Andy K-D, assistant cameraperson and IATSE member. The authorized IATSE strike, a historical first for “the union behind entertainment” with some 150,000 members, is still hanging in the balance between a negotiated arrangement and the membership approving it. Andy details his highly technical, highly stressful labor - but thankfully, with a crew and a union.

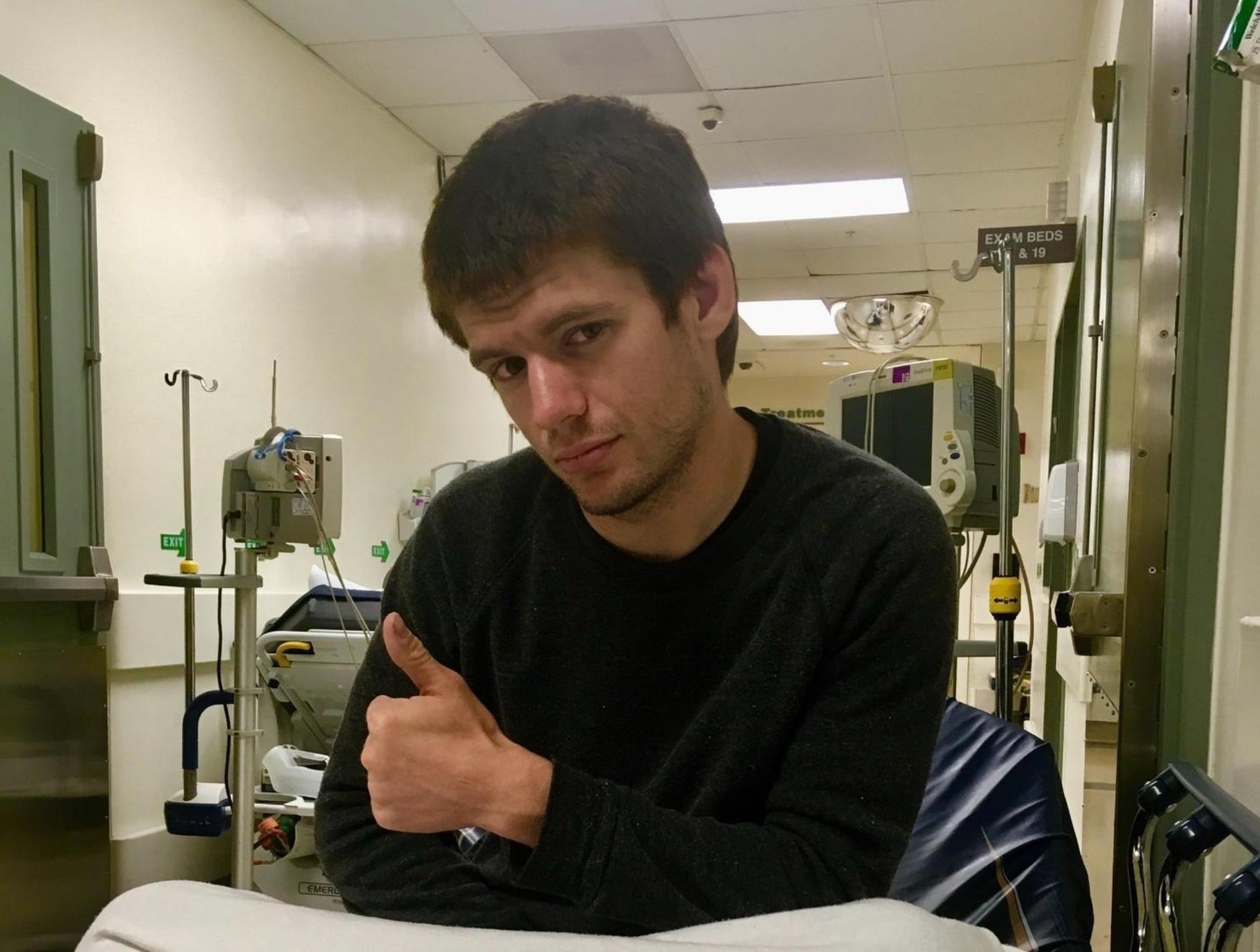

Andy in the hospital after getting electrocuted on set after a 14 hour day.

The Worker’s Perspective

by Andy K-D

I entered film school right when I turned 18, in the wake of the financial crisis and the subsequently dismal job market, which was terrible for the entertainment industry. But I decided to go into film because I heard there were unions and that I could earn $25-30 per hour, and I didn’t know anyone who was making that much – not even my film professors. I’m 29 now and I’ve worked in film since I was 18. I was an unpaid intern, a PA, a grip with IATSE 487, and eventually an assistant in Local 600.

My job is second assistant cameraperson. This means I manage the camera equipment. I change the batteries. I put the marks on the ground for actors to position themselves. I make the report. I help to figure out what gear is necessary for a shot or scene. I keep the camera ready for change at a moment’s notice so we can do anything. I’m always on set and always necessary.

People who work in the cinematographic arts have highly technical jobs. You can get some muscle memory, but every day you have different circumstances with a different set, a different scene with a different actor who moves in a different way. Even if we’re set up, if an actor’s mark needs to move during lighting, I need to be within an arm’s reach to move it. We have at least five things with batteries that I have to change on the fly. I have to be present to change a lens of a filter at a moment’s notice. On most jobs, I can’t really leave the set for the entirety of the day.

In the times of COVID, working 14 hours in a KN-95 mask and a face shield is extremely uncomfortable, and with these additional conditions, they don’t give us more staff. They tell us we can’t eat or drink water on set to protect our safety, but if I walk outside I hear, “Andy Andy Andy” or “mark mark mark we need to change a mark.” The culture of the set is like this: if I ask to get a drink of water, someone will say “yes” but realistically, I can’t. Since getting into film, I’ve gotten kidney stones seven times. I’m 29 years old. It’s ludicrous.

Doing this work all over the place is exhilarating in some ways. You don’t get scripts or schedules or plans ahead of a job, you just get a range of dates and say yes. You get text messages, “Are you available November 14th to January 23rd for a show?” And you reply, “Well, I live in Glendale, where is the shoot? What will the hours be?” And they say, “Still being decided.” And you just have to have the grit to say, “Yes.”

Every day, you just have to be prepared for that day to be the worst day of your career. Rarely does anyone have information about what tomorrow will bring, but you prepare for every scenario. You have a 5 person scout, you have a crew booked, and you just show up with a bunch of 10-ton trucks and figure it out. We’re asked to do this incredibly technical job in the middle of a very stressful environment that you have no control over. They say wrap when they’re ready. You can’t make that call for yourself to go home. They don’t tell you where the finish line is. If you finish 2 hours ahead of schedule, they just add more work because it’s in the budget.

As a cameraperson I work closely with focus pullers whose job it is to adjust a knob and work with a tiny motor every second of the day moving the focusing element of the lens while watching a 17” monitor, 14 to 16 hours a day. It’s similar to doing other computer work in that you’re forced to stare at a monitor constantly as complex variables change. Imagine taking your workstation to the top of a cold mountain, after hiking, and then being asked to code at a very high level. And nobody else could do your job on the set, but the instant you fuck it up for one second, you hear it bellowed over the set.

In film, it’s really hard to come down from the highly technical nature of the work we do all day. When you’ve been so amped and caffeinated to stay sharp through a long day, and now it’s late at night and you’re tired after so many days and nights, and you get in this warm quiet car… your brain just shuts down. So you have to take a shot of espresso at 4am and hope that keeps you awake, but your ability to make safe, reasonable decisions is impaired by carcinogenic hours. I’ve got a bag of clothes and a pillow in the back of my car, and I’ve only been in one major car accident, but hundreds of people have lost their lives because they drove drowsy. Yet, we just pretend that it’s normal because the people who set the terms of our employment say that it’s normal.

We have these incredibly tight turnarounds where we get 9 hours or 10 hours on the contract. You could work LAX one day and Santa Clarita the next and they don’t have to give you an extra minute of turnaround. With the commute, you end up being home for 6 or 7 hours to get family, food, and sleep and meanwhile you’re super caffeinated and have to try to immediately fall asleep. People end up drinking themselves to sleep and have long term substance issues or are woefully underslept. They neglect their families in an attempt to steal themselves to provide for their families. But as long as the project comes in under budget and under schedule, it was a success.

The film industry acts like labor history never happened. We live in this fantasy that the carpenter guilds didn’t fight for a 10-hour day in the 1830’s, that the Haymarket riots didn’t happen for an 8 hour day. In the consolidation of the Hollywood unions into IATSE in the 1950s, the studios crushed the more progressive so-called “socialist and communist” unions and IA guaranteed the film crews would never strike again. The LAPD and WB security beatings of Hollywood Black Friday led right to the Taft-Hartley Act and was the direct influence of the Red Scare, George Meany and the AFL-CIO consolidation. Below the line filmworkers haven’t had a major labor action since.

But the internet has galvanized us in ways to talk with each other. On set, you have to maintain composure and not show any weakness even if you’re on the edge of a breakdown. The internet allows us to air grievances in a huge way. And as soon as you hear a traumatic story you think, oh yeah, that happened to me too. And you realize that we’re all really on the same page.

I’ve seen attitudes change, as our working conditions are getting more and more ridiculous. As workers are being pushed over the edge, you see more and more of us being open to speaking out. The businesses say they’re injecting 30% more into productions to cover COVID protections but they never use funds to improve our conditions. They haven’t restored night premiums, or time off to rest and recover. They maintain that they can’t improve things but, as publicly traded companies, we can see that they’re immensely profitable. We see them raking in record profits and diverting funds away that are rightfully ours at the expense of the health and safety of our coworkers.

This summer I worked on a job for Disney about a major tech company founding, chronicling the crush that happens and the mental health crunch of a lot of tech workers. Characters within the show are overworked to the point of self harm. The production company that took up the production made an impossible schedule because they had another show to do shortly after. Day 1 was a 14-hour day, and they didn’t finish the scheduled daily work for the first two weeks of the job; there was always another page or two to go. We would shoot until they hit minimum turnaround (10 hours). Basically, they would get to a point where they would have to pay us more and then let us go.

We were told to work faster by producers who have zero technical experience. They’d watch us work on Zoom because they say it’s not safe to be on the set. They’d text notes to redo hours of work deep into our days. The schedule shifted constantly into nights, with 14 straight fraturdays (Friday shoots which bleed into Saturday morning) and we constantly had to catch up on unfinished work. It was a bit miserable. However, we had a very strong crew. We had an incredibly talented female DP, the director of photography, that kept spirits high and kept us producing beautiful work every day with our wonderful actors, getting skilled, artful work done under unreasonable conditions. We did this for three months, constantly expressing that this schedule is unreasonable, but the conditions didn’t change because the studio had agreed to the schedule.

The discontent of the crew, the brutal hours, and the ever lagging schedule were responded to not by admitting a scheduling mistake and adjusting, but by firing the cinematographer, the one person we all liked who kept the work doable. They didn’t talk to the crew and ask how we felt or even tell us they fired her in a back room after another 14 hour fraturday. They never sent an email or phone call or anything to the crew. So, the whole camera department decided to pack their stuff up and head home. Wildcat strikes are illegal, but quitting isn’t striking. Collectively walking out and saying goodbye and good luck is well-protected.

I’ve learned that collective action through your union is very important, but you can organize within your crew or set to demand things of production, even within 2-3 weeks. Creating cross-craft collaboration to fight back is so important and having formal or informal stewards on set is essential. I think if we’re going to create a culture to stop brutal working conditions, we have to take our lives into our own hands and show production that we’re willing to take action. We have to be able to stand up and say, This is bullshit. We make the films, and we’re out.

For more worker’s perspectives in IATSE and strike updates, follow @IA Stories on Twitter or @IA Stories on Instagram. Thank you to Sunny Rao, Danny Spitzberg, and the TWC crew for the conversation and solidarity.