Abolitionist Cybernetics: Groceries from South Bay Mutual Aid

25 Jan 2022

People need groceries. Mutual aid projects need systems. Today, Erik talks about architecting the South Bay Mutual Aid project and volunteer network, which has helped move nearly $80,000 in groceries, diapers, and PPE to San Jose residents. It surfaces the formal and informal structures in any organizing effort, which cybernetics comrade Stafford Beer characterized for Chile’s socialized economy many decades ago. The ongoing effort demonstrates how tech systems work best with autonomy, accountability, and active efforts to counter the corporate nonprofit tendencies we pick up.

A fractal photo collage of cybernetics and socialized systems, featuring volunteers in South Bay Mutual Aid. If you look closely, you can see that movements grow with people and organizations laying out what has been accomplished, so that others can interpret and apply past lessons to their own circumstances.

The Worker’s Perspective

By Erik

Image VS Reality in Silicon Valley

In 2018, I quit my job as an operations engineer and took a position washing dishes on a major tech campus. Having grown up around Silicon Valley, I’ve seen first-hand how tech industry wealth is built on the backs of the poorest, from tech campus janitors to food delivery workers making below minimum wage. This perspective can be disheartening, but I believe the small distance between these extremes is a weak point in our economy – and participating in mutual aid can build a path to bringing these worlds together, while also overcoming shame, undoing fear of failure, and preventing burnout.

My organizing experience also revolves around tech. It’s a response to how the industry’s growth impacts those who live and work here, and how the products impact the rest of the world. There is a powerful organizing scene in Silicon Valley that punches above its weight: organizers fought against San Jose when the city sold out public resources to Google, and we campaigned to make Palantir so unwelcome that they relocated their headquarters. We can push back against the worst of the industry, and win.

My introduction to mutual aid was witnessing the grassroots response to the 2018 Northern California Camp Fire. People came together on a large scale in the face of tragedy, showing widespread awareness of how interdependent we are. Unfortunately, it also showed how easily such goodwill could be co-opted by moralistic narratives. Mutual aid provided direct money and resources to people who had lost their homes in the fire, many of whom descended into Chico, which like most cities in California had its own unhoused population. Some of the mutual aid efforts implicitly separated the two groups, viewing one group as legitimate victims and the other as undeserving of even charity. And yet climate change and homelessness are disasters arising from the same root cause: a small, shrinking group gaining power and wealth to our collective detriment.

The beauty of mutual aid lies in its simplicity. The approach to solving an acute disaster can be applied to take on the larger ones: Something terrible happened, so what do people need, and how do we take care of them? I observed common tendencies and structural problems, including burnout and power consolidation, across various mutual aid efforts. Promising efforts can slide backwards and revert to top-down, unaccountable models, which is why organizers need to think about these efforts systemically. To make mutual aid sustainable, we need systems that empower as many people as possible to get involved and do the work, share the load, and grow the effort at scale.

Mutual Aid and Systems Theory

When a large-scale disaster like COVID hit, organizers in San Jose and beyond knew how to respond, based on recent experience overcoming uncertainty and government inaction. We wanted to use our capacity to help others who were facing layoffs, illness, and other issues. As more people became involved, these efforts were formalized into South Bay Mutual Aid. While many projects operated under this umbrella, including N95 mask giveaways and unhoused outreach, the largest was the survival grocery delivery program for Santa Clara County, an alternative to local state sponsored programs, such as Catholic Charities or Second Harvest Food Bank. In the year after the coronavirus hit, SMBA was able to redistribute $70–80K worth of groceries and other neccessities.

While mutual aid and charity can look similar in practice, charity often exacerbates the problems it purports to address, from placing arbitrary conditions and requirements on those who receive help, to paying their own workers poverty wages. Charity is the powerful passing out a fraction of their wealth to those they deem worthy, while mutual aid means sharing what we have to ensure our own survival and ultimately topple that divide entirely.

Our mutual aid effort didn’t gather any demographic data on those receiving aid other than where groceries were dropped off. The vast majority of goods went to Central and East San Jose, and to various pockets of rent-controlled apartments scattered across the valley. Unsurprisingly, these areas hardest hit by COVID are also the places most negatively impacted by the tech industry, both being at risk of tech-fueled gentrification, and being where its service workforce lives.

In order to design systems for our work, we used concepts from management cybernetics, pioneered by British theorist Stafford Beer in the mid-20th century. Cybernetic systems can be described as processes for maintaining equilibrium, with examples that can be found throughout the natural and human worlds, from individual biological systems to organizations and self-replicating social structures. The viable system model has five levels, each with specific tasks and relationships to the other levels and outside bodies, which work together to steer a system without the need for leadership. The large-scale implementation of this theory, in partnership with the government of Salvador Allende, was an attempt to use early computer networks and build feedback loops in order to run the Chilean economy. Although this project showed great promise, it was ultimately unsuccessful after a US-backed military coup toppled the democratically-elected Allende government in 1973 and installed a military junta which ran the country for the next 25 years. This is foreshadowing.

Applying cybernetic analysis to universal human needs like food and shelter, we can imagine systems for meeting our needs outside of capitalism. To make this real, we have to start with small-scale local needs. For our own implementation of management cybernetics, we divided the work into two systems, with “System 1” referring to the day-to-day practices that help the community, and “System 2” referring to higher-level functions. System 1 is praxis, theory in practice. Any project responding to community requests can use a similar system: weekly food distribution like the long-running group Food not Bombs, prisoner support and phone zaps, providing aid for workers or tenants or homeless populations, even building a neighborhood Wi-Fi network.

System 1: grocery delivery, an example of direct services responding to community requests

In our implementation of System 1, we were able to assess people’s needs in the community in a straightforward way: an online form, first hosted on Google Sheets, and later moved to Airtable in order to accommodate a higher volume of requests. Because of COVID, many potential volunteers were not comfortable providing in-person help, so to accommodate this we developed a two-step process to respond to these requests. Members of the aid coordinator team, working from home, could view outstanding tickets and respond to the ones they felt most comfortable with based on languages spoken, location, and so on. Aid coordinators could then get a list of items for delivery or point them to other services if they had needs beyond that. If they needed groceries delivered, the aid coordinator would reach out to a list of volunteer delivery drivers to find a willing volunteer in the area. The list of items was passed on for the driver to pick up and drop off, and then the driver could request reimbursement through a financial portal. No requirements or quotas were imposed on coordinators or delivery drivers, so volunteers were free to participate as much or as little as they chose, based on their own comfort or schedule.

The coordinator task of responding to these requests quickly became the most challenging role. Many of us, myself included, didn’t have experience with this sort of contact, and it could be especially painful when the needs were beyond what we could provide. The team met weekly to discuss challenges and provide support for one another, and as more people became involved, a sustained community began to form.

One purpose in getting people involved with this type of service work is building a movement around your specific material goals. Power comes when the widest range of people can participate and see the value in your work, and can draw from their own background and experience to find new and better ways to support it. Mutual aid efforts can draw a wide range of people, including lifestyle activists – those who throw around political language without putting in much work – and people who may have little political education or use reactionary language but who are always willing to help out. If you listen and consistently deliver on a community need, you will naturally build a constituency that can be further organized. For example, people who are asking for help with groceries might also need help organizing against their landlord or their boss.

Direct contact with the community also connects this power to accountability. Your legitimacy comes from your ability to serve. People are extremely receptive to being further organized by those who have already demonstrated a willingness and ability to meet their basic needs. Conversely, attempting to further organize without being able to meet these needs is the organizational equivalent of biting off more than one can chew, at which point you may need to refocus on the fundamentals. Providing hot meals to people is unambiguously good, but unless they can be provided on a regular schedule, people will still have to worry where their next meal will come from. At the beginning of the project, we had volunteers cooking and delivering meals, but with the amount of labor required we realized that outside of a disaster situation, it made a lot more sense to provide groceries or direct financial support.

System 1 work brings acute awareness of others’ struggles, and directly works to break down the ego and build political consciousness. Many existing programs to help people with food or shelter I previously thought were available either required untenable hurdles to access or simply didn’t work. After an illegal eviction, one person I met would have been forced to euthanize their pet – their only companion – in order to access a few days at an emergency shelter. One person requesting groceries was already signed up for a program through the city, but so far had only received boxes of rotten produce. Direct service brings us closer to the real-time cycles of human needs that must be addressed if we want to build power and change our current circumstances. Hunger and need for shelter have hard deadlines that we either meet or we don’t.

Leadership Comes From Below

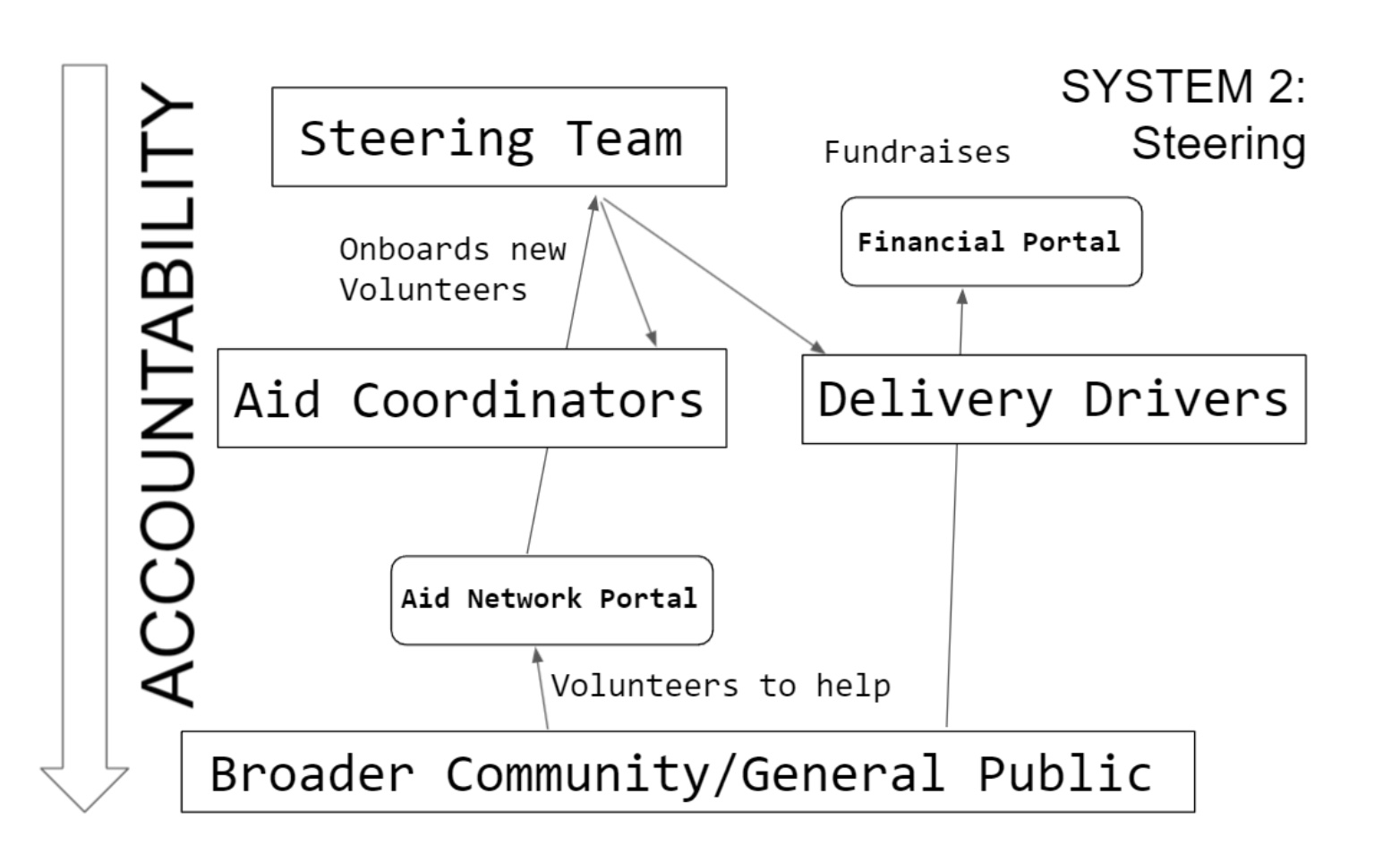

System 2 is for higher-level functions. How well these functions are implemented can determine whether the project grows or fails. Because higher-level functions are not directly tied to community needs, the systems of accountability are not always naturally occurring, but where they don’t exist, they need to be built. There is no template for how they will look, but generally, as many people as possible should be trained and comfortable performing any system function. Access to meeting spaces, finances, social capital and online clout – all can constitute single points of failure. Ideally, no one should feel unable to step back without it causing an impact.

Similar to System 1, creation of a self-sustaining program will come from bringing the widest and most diverse perspectives together around how to best support those doing on-the-ground work, rather than managing. In my experience, higher-level duties are best run by those who have been involved in lower-level work, but even when not, should be governed by the dictates of those on the ground level. The most common issues I’ve seen in organizations arise when reproductive labor isn’t recognized, as people in difficult roles will quickly leave when they feel their efforts aren’t being respected. Within our project, the strongest sense of solidarity and building of community came when those involved with steering were intentional about celebrating the individual contributions necessary for the project to function. System 2 efforts like recruitment, fundraising, social media, finances, outreach, etc. may be higher level, but need to be first and foremost accountable to the organizational System 1 purpose (or purposes). As this system grows, its functions should continue to operate even as the lines between individual roles blur.

System 2: steering, a form of supporting and providing resources for System 1

Unfortunately, because System 2 functions can be performed without direct community input, mutual aid formations face co-optation in subtle ways, like letting established organizations control the flow of funds. There is real danger that fundraising and recruitment become their own program, removed from the context of the service work needing to be done, by a small number of self-selected activists. Consolidation of power and responsibilities falling onto a few individuals, even with the best of intentions, will inevitably lead to burnout and breakdown. And from the perspective of those doing on-the-ground work, and those being served, there is very little difference between resources not being distributed in a timely manner and being withheld outright.

Anyone embarking on mutual aid projects, especially with relative privilege, should aim to facilitate the redistributive process in a way that those with the greatest understanding of the need can eventually run it. In practice, this means being aware of organizational choke points and making sure that work is distributed and can be taken on by anyone willing to make the effort. Any sudden influx of resources should be a growth opportunity; the world we exist in has absolutely no shortage of need.

Many people who participate in mutual aid work are not explicitly anarchists, which also speaks to the universality of support we encountered that political projects aren’t always able to capture. The goal isn’t to work towards a specific outcome or to build an organization, it’s to build a process. We can be working towards an anarchist mutual aid-based society, building dual power counter to the existing state, or simply creating systems of care; at this level it doesn’t matter. Ultimately we want to build a culture capable of survival and growth outside of capitalism: a better way of living. This sort of work comes far more naturally to those involved in schools or churches, rather than activist circles.

Mutual aid work is simple, but still difficult. People come into this work for various reasons and don’t all get the same thing out of it, yet that’s exactly how we start to recognize this movement as something bigger than ourselves. Not every project will succeed, but no project will fail; these are all opportunities for learning about which systems serve us, and how to improve them as an even stronger foundation for their work. Failure can only come when we refuse to acknowledge missteps and continue to reproduce unaccountable, oppressive systems – sometimes of our own design.

At its core, mutual aid is the belief that no matter how well we may do as individuals, collective survival requires collective wellbeing. We may not be victims of the latest natural or economic disaster, but the individualist fantasy of escaping to a bunker holds us back from accepting the fact that eventually we all have to ask for help.

Thanks to Sunny, Tamara, Danny, Jonathan, and Wendy for the discussion and editing that resulted in this piece. If you’re interested in learning more cybernetics and mutual aid, check out Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next), Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile, and your local mutual aid effort. Countless projects need support at this moment, but if you have cash burning a hole in your pocket I’d suggest dropping it with Subvert UD, a coalition of students and community members providing hot meals and survival gear to residents of Seattle’s University District, and North Beacon Hill Mutual Aid, an organization providing aid and political education to unhoused communities in Beacon Hill.